Deacon William T. Ditewig, Ph.D.

[Posted here with permission. It will be published in the next issue of OSV’s The Deacon.]

This essay is, in many ways, a kind of lament. Many of us have written extensively on the disappointing and even disheartening lack of deacons in attendance at the first General Assembly of the Synod either as participants or as theological or canonical consultants. As hurtful as it is, we must certainly continue in our wonderful and grace-filled ministry to those most in need around us. To grieve over missed opportunities does not relieve us of those obligations.

My mentor at the Catholic University of America, Father Joseph A. Komonchak, has written and spoken often of the gap between the glorious words we sometimes use to describe the Church, and the reality of the Church as many people experience it. He wrote, “If there is a single question that has haunted me for the forty years that I have now been teaching ecclesiology, it concerns the relationship between the glorious things that are said in the Bible and in the tradition about the Church – ‘Gloriosa dicta sunt de te, civitas Dei!’ (Ps 86:3) – and the concrete community of limited and sinful men and women who gather as the Church at any time or place all around the world.” He described how people’s eyes “seemed to glaze over when someone spoke of the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’ or ‘Mother Church’ or ‘Bride.’ Theologians might have found it interesting to explore such notions, but what could they have to do with the people in the pew?” In this essay, then, we will “mind the gap” between those “gloriosa dicta” about the diaconate along with the frequent “de profundis” (Ps 130:1) sometimes experienced by the Church’s deacons.

Ah, the gloriosa dicta!

Throughout the patristic literature we find repeated references to the deacon serving “in the very ministry of Christ,” that the relationship of the deacon and bishop should be like the relationship between God the Father and God the Son, and that the deacon should be the eyes and ears, heart of soul of the bishop, that deacon and bishop should be like “one soul in two bodies.”

In our own time, we have the language of Vatican II, which includes the statement that diaconal duties are “ad vitam Ecclesiae summopere necessaria” – supremely necessary to the life of the Church. The Council continues by describing the diaconate itself as “a proper and permanent grade of the hierarchy.”

Moving beyond the Council, popes and theologians continued to say glorious things about the diaconate. Pope Paul VI referred to the diaconate as the “driving force” for the Church’s service, and Pope St. John Paul II repeated that description before adding that the diaconate is “the Church’s service sacramentalized.” Church documents and the work of contemporary theologians built on that language, using terms like “the deacon is an icon of Christ the Servant”, while James Barnett’s classic work on the diaconate refers to us as a “full and equal order.” Another early text even makes the claim that, “A parish, which is a local incarnation of Church and of Jesus, is not sacramentally whole if it is without either priest or deacon.”

Such marvelous and glorious and humbling words! A lexicon of service to inspire and drive the diakonia of the Church!

But then, de profundis….

But is this how deacons experience things in their daily exercise of ministry? Is this how the lived reality reflects these glorious words? Is this how our parishioners and fellow ministers, lay and ordained, see us? If it is, praise God! If it isn’t, what can we do, as the English say, to “mind the gap” between theory and practice? Deacons are happy and fulfilled in their various ministries, while at the same time, there are stories of presbyters, religious, and laity who do not seem to “get” the diaconate and even, in some cases, are antagonistic toward it. Deacons report instances where pastors “don’t want” the bishop to assign a deacon to the parish, and still other cases where deacons are accused of perpetuating clericalism in the Church. Still others have been told that “the diaconate isn’t a true vocation.” In short, the gap between the gloriosa dicta of theory and the de profundis of praxis is, in many cases, wide and deep. And so we come to the question: how might we close the gap?

Enter the Synod on Synodality.

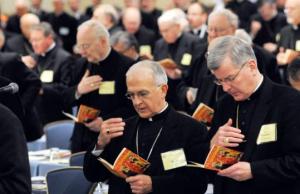

What an opportunity for representatives of all God’s People to gather and discern together the future of the Church! But when the time came to assemble for the 16th Ordinary Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, where were the deacons?

Certainly, the Synod Secretariat faced a massive challenge: ensuring participants and consultants representing the universal Church in all its richness of laity, religious, and clergy. Delegates were chosen by episcopal conferences, from the Eastern Catholic Churches, selected leaders from the Roman Curia, and 120 delegates personally selected by Pope Francis. In total, 363 people were voting members, including 54 women. In addition to the voting members, 75 additional participants acted as facilitators, experts, or spiritual assistants. Wonderful!

And one deacon. (Actually, two: one was from Syria about to be ordained to the presbyterate.)

There were other lacunae. Many observers noted the lack of parish priests, the poor, and even the lack of substantive influence of the assembled theological consultants when contrasted with the influence of the periti at the Second Vatican Council. But nowhere was the inequity more glaring than that of the diaconate. Imagine a group of men calling a meeting to talk about women, but with no women present. Imagine a meeting about the priesthood, with no priests participating. And imagine a meeting about the diaconate with no deacons. In a choir, each singer has their own voice, and yet each one must listen to the others to form beautiful harmony. If the Church were a choir, the same applies: everyone would have a voice, while listening to all the other voices. Deacons have been told, in glorious terms, that they are part of the choir. But, in terms of the Synod, they have no voice. In a choir, is it better to talk about a tenor or to hear one? In the church, is it better to talk about deacons, or to hear them?

Someone seems to be listening, at least about the lack of parish priests at the Synod. The Synod Secretariat has announced recently an extraordinary 5-day gathering of some 300 priests convening in late April. According to the Secretariat, this is to respond to the desire of the Synod participants to “develop ways for a more active involvement of deacons, priests, and bishops in the synodal process during the coming year. A synodal Church cannot do without their voices, their experiences, and their contribution.” The announced gathering is therefore good news. But once again the question recurs: Where is the gathering of the deacons?

Once again, there is the gap between glorious words and actual practice. When you tell someone that they are valued and that “their voices, their experiences, and their contribution” are vital, and then do nothing to open the door to those voices, why should the nice words be believed? To be excluded again, after the gap is pointed out, feels hurtful and dismissive, conveying clearly that deacons have no voice worth hearing, no experience worth sharing, and no insights to give or to receive. It sends the clear message that deacons are unnecessary, with nothing to contribute. The gap between “gloriosa dicta” and “de profundis” remains.

In conclusion, what may be done? Some will rightly say that none of this impedes our responsibility to care humbly for others and that we do not need a seat at the Synodal tables. I fully affirm the first part of that claim. But serving does not mean we should not also have a share in the Synodal process. As I have suggested elsewhere, perhaps one course of action might be to have conversations within our own parishes and dioceses and pass those insights along to our bishops. Perhaps theologians and canonists might direct the results of their research on the diaconate to the Synod Secretariat for their use. No matter what we do, however, we must do everything we can to bridge the gap between words and actions. As heralds of the Gospel, we can do no less.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION nothing new, although he has been particularly passionate in reminding the world of the moral principles involved.

nothing new, although he has been particularly passionate in reminding the world of the moral principles involved. THE ADDRESS OF POPE FRANCIS

THE ADDRESS OF POPE FRANCIS To Welcome

To Welcome To Promote

To Promote To Integrate

To Integrate 3. Solidarity

3. Solidarity

As I write this, reports are coming in from Baton Rouge about yet another attack with multiple casualties. The world is reeling from the endless chain of violence and death of recent months. On Friday, the PBS series Religion and Ethics Newsweekly ran a program on the Order of Deacons in the Catholic Church. Given the state of the world, one might think this an odd or even irrelevant topic. Upon reflection, however, I believe that there are some important dots to connect. It is precisely because of the current state of violent death, destruction and havoc that the diaconate — properly understood — might offer a glimmer of hope. After all, it was precisely because of the “abyss of violence, destruction and death unlike anything previously known” (John Paul II, referring to World Word II) that the Order of Deacons was renewed in the first place; we’re here to help do something about it. So we shall review the PBS story against that critical backdrop.

As I write this, reports are coming in from Baton Rouge about yet another attack with multiple casualties. The world is reeling from the endless chain of violence and death of recent months. On Friday, the PBS series Religion and Ethics Newsweekly ran a program on the Order of Deacons in the Catholic Church. Given the state of the world, one might think this an odd or even irrelevant topic. Upon reflection, however, I believe that there are some important dots to connect. It is precisely because of the current state of violent death, destruction and havoc that the diaconate — properly understood — might offer a glimmer of hope. After all, it was precisely because of the “abyss of violence, destruction and death unlike anything previously known” (John Paul II, referring to World Word II) that the Order of Deacons was renewed in the first place; we’re here to help do something about it. So we shall review the PBS story against that critical backdrop. THE PBS PROGRAM: Religion & Ethics Newsweekly

THE PBS PROGRAM: Religion & Ethics Newsweekly “In the Middle Ages the role of deacons began to fade as the power of priests and bishops grew. In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council restored the role of deacons – but only for men.” The evolving role of deacons throughout history is far more complicated than that, and overlooks the fact that the diaconate never completely disappeared, but became primarily a stepping stone to the priesthood. I fully acknowledge that the history of the diaconate in all of its complexity goes far beyond what can be covered in such a brief program, but still: the broad brush strokes of the history could have been recognized and acknowledged. This is also when the program shifts to the question of the possibility of ordaining women as deacons. I will deal with that question below.

“In the Middle Ages the role of deacons began to fade as the power of priests and bishops grew. In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council restored the role of deacons – but only for men.” The evolving role of deacons throughout history is far more complicated than that, and overlooks the fact that the diaconate never completely disappeared, but became primarily a stepping stone to the priesthood. I fully acknowledge that the history of the diaconate in all of its complexity goes far beyond what can be covered in such a brief program, but still: the broad brush strokes of the history could have been recognized and acknowledged. This is also when the program shifts to the question of the possibility of ordaining women as deacons. I will deal with that question below. Now, on the PLUS side:

Now, on the PLUS side:

So, what is the connection? How can the diaconate be understood against that much larger and violent backdrop? The most important question of all is perhaps, why do we have deacons in the first place?

So, what is the connection? How can the diaconate be understood against that much larger and violent backdrop? The most important question of all is perhaps, why do we have deacons in the first place? In our time, as I’ve written about extensively, the Second Vatican Council decided overwhelmingly that the diaconate should be renewed as a permanent ministry in the church once again, even to the extent of opening ordination to married as well as celibate men. The bishops in Council did this largely because of the insights gleaned from the priest-survivors of Dachau Concentration Camp. Following the war, these survivors wrote of how the Church would have to adapt itself to better meet the needs of the contemporary world if the horrors of the first half of the 20th Century were to be avoided in the future. Deacons were seen as a critical component of that strategy of ecclesial renewal. Why? Because deacons were understood as being grounded in their communities in practical and substantial ways, while priests and bishops had gradually become perceived as being too distant and remote from the people they were there to serve.

In our time, as I’ve written about extensively, the Second Vatican Council decided overwhelmingly that the diaconate should be renewed as a permanent ministry in the church once again, even to the extent of opening ordination to married as well as celibate men. The bishops in Council did this largely because of the insights gleaned from the priest-survivors of Dachau Concentration Camp. Following the war, these survivors wrote of how the Church would have to adapt itself to better meet the needs of the contemporary world if the horrors of the first half of the 20th Century were to be avoided in the future. Deacons were seen as a critical component of that strategy of ecclesial renewal. Why? Because deacons were understood as being grounded in their communities in practical and substantial ways, while priests and bishops had gradually become perceived as being too distant and remote from the people they were there to serve. The diaconate today, fifty years after the Council, has matured greatly. Those who would talk intelligently about the diaconate need to keep that in mind. Over the past fifty years, formation standards have evolved to better equip deacons for our myriad responsibilities, for example. The diaconate has, at least in those dioceses which have had deacons for several generations, become part of the ecclesial imagination. In some dioceses we have brothers who are deacons, fathers-in-law and sons-in-law who are deacons, fathers and sons who are deacons. In one archdiocese, an auxiliary bishop is the son of that archdiocese’s long-time director of the diaconate. As I mentioned above, the diaconate looks and feels different from one diocese to another and while it is tempting to generalize whenever possible, it is particularly dangerous.

The diaconate today, fifty years after the Council, has matured greatly. Those who would talk intelligently about the diaconate need to keep that in mind. Over the past fifty years, formation standards have evolved to better equip deacons for our myriad responsibilities, for example. The diaconate has, at least in those dioceses which have had deacons for several generations, become part of the ecclesial imagination. In some dioceses we have brothers who are deacons, fathers-in-law and sons-in-law who are deacons, fathers and sons who are deacons. In one archdiocese, an auxiliary bishop is the son of that archdiocese’s long-time director of the diaconate. As I mentioned above, the diaconate looks and feels different from one diocese to another and while it is tempting to generalize whenever possible, it is particularly dangerous. Here is my point: If we deacons were restored in response to Dachau and similar world shattering violence, translate “Dachau” to Baton Rouge. “Dachau” to Nice. “Dachau” to “Black Lives Matter”. “Dachau” to 9/11. “Dachau” to every act of senseless terror and random violence. What are we doing to confront these tragedies? What are we doing to work toward a world in which THEY can no longer exist? This is so much more than who gets to exercise “governance” (a technical canonical term) in the Church, or who gets to proclaim the Gospel in the midst of the community of disciples.

Here is my point: If we deacons were restored in response to Dachau and similar world shattering violence, translate “Dachau” to Baton Rouge. “Dachau” to Nice. “Dachau” to “Black Lives Matter”. “Dachau” to 9/11. “Dachau” to every act of senseless terror and random violence. What are we doing to confront these tragedies? What are we doing to work toward a world in which THEY can no longer exist? This is so much more than who gets to exercise “governance” (a technical canonical term) in the Church, or who gets to proclaim the Gospel in the midst of the community of disciples.  I hope that there will be more media programs on the diaconate. I hope that not only will they be done accurately, but that they will also be done with a sense of the vision and potential of the diaconate.

I hope that there will be more media programs on the diaconate. I hope that not only will they be done accurately, but that they will also be done with a sense of the vision and potential of the diaconate.