Initial Reflections on Deacons and Priests in the Summary Report of the

First Session of the XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops

For the nurturing and constant growth of the People of God, Christ the Lord instituted in His Church a variety of ministries, which work for the good of the whole body (Lumen Gentium, 18).

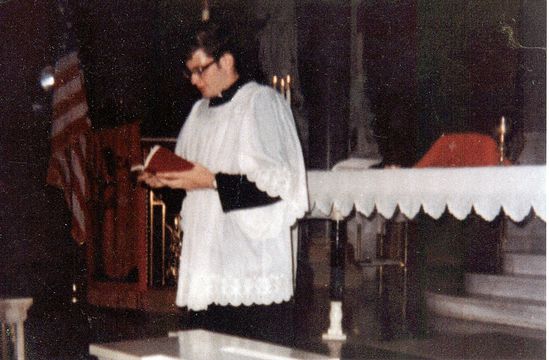

Introduction: Memories

The old man was tired. We had been conducting a series of interviews over several weeks, and today’s interview had drained him as he recalled people and events from decades earlier. But the last two questions had re-energized him as he shifted in his chair and leaned forward to respond. “Bishop,” I had asked, “two more questions. First, for many years, you used to talk about the Second Vatican Council all the time. In recent years, however, you rarely talk about it. Why not? Second, are there issues that you think the Council Fathers overlooked or did not emphasize as much as they should have?”

The bishop was the bishop emeritus of a Midwestern diocese. He had attended all four sessions of Vatican II as a young newly ordained auxiliary bishop. He had agreed to these interviews as an essential contribution to the oral history of the Council. His responses to these questions were particularly poignant.

“Well, Bill, I’ll tell you. Your two questions go together. The answer is one word: the priesthood.” He explained that, after the Council, he had enthusiastically embraced the implementation of the Council. He created a Diocesan Pastoral Council, restructured and expanded his diocesan staff, and personally spread the news of the Council throughout the diocese. However, not many years after the Council, the dwindling number of priests became a torrent, and the number of seminarians plummeted. As the years passed, the bishop began to wonder if something they had done at the Council – or not done – was responsible. It dawned on him that while the Council had done some wonderful things, perhaps they had missed something.

On the one hand, they had called all people to perfection in holiness, obliged the laity to greater participation and co-responsibility for the Church, advanced their own understanding of the nature of episcopal ministry, addressed reforms in religious life, and even revitalized a diaconate permanently exercised. But the world’s bishops had not addressed the priesthood in any substantive way. The bishop said that the very group who would be responsible for the ongoing pastoral implementation of so many of the Council’s decisions were not consulted in advance, were not represented in the conciliar debates, and were not properly formed and informed to actualize the vision and realize the potential of the Council. The bishops had assumed the overall stability of the nature and ministry of the priesthood. Until his death, the bishop agonized over this lacuna and its effects.

The 16th Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops

This memory came to mind while reading the Synthesis Report of the 16th Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops. This essay will focus on Section 11 of the Report, titled “Deacons and Priests in a Synodal Church.” Before beginning, however, I want to be clear: I could not be more excited about Pope Francis and his call to recognize, affirm, and expand the synodal character of the Church. For the pilgrim church described by Vatican II to continue on its way to the Kingdom, a “synodal path” is essential. However, if the Synod were a choir, I believe some voices would be missing.

By all accounts from those who were there, the 2023 General Assembly was a positive and exhausting experience. The Synod Secretariat at the Holy See faced a Herculean challenge: identifying participants and supporting players representing the universal Church in all its rich tapestry of laity, religious, and clergy. Delegates were chosen by episcopal conferences, from the Eastern Catholic Churches, selected leaders from the Roman Curia, and 120 delegates personally selected by Pope Francis. In total, 363 people were voting members, including 54 women. In addition to the voting members, 75 additional participants acted as facilitators, experts, or spiritual assistants. From a planning perspective alone, the Synod office did a yeoman job of pulling together an impressively diverse team of participants.

At the same time, many observers have noted significant lacunae in the participant list. There were, for example, only two deacons in the assembly, one a deacon from Belgium and another from Syria who is about to be ordained a presbyter. Others point to a serious lack of parish priests in the Assembly. Still others highlighted the absence of the poor, and other commentators have noted the lack of substantial influence of the theological experts attending the Assembly when contrasted with the significant impact of theological and canonical periti at Vatican II. All of these areas, and more, are worthy of additional analysis and study. This essay’s focus on Section 11 should not be understood as suggesting these are the only or even the most notable areas for investigation. The purpose of synodality is to journey together, listen, share, and discern together. It seems that if one finds oneself talking about someone else rather than with someone else, then a structural weakness in the process has been found. Consider a well-known example.

Some years ago, the USCCB worked on a draft document on the role of women in the Church. It went through many drafts, listening sessions, and more drafts. Finally, after years of effort, the bishops scrapped the project. The bishops realized that the document was talking about women and the Church as if they were two distinct things: women on the one hand and the Church on the other. If a group of men called a meeting to talk about women, and no women were part of those conversations, we would immediately see the weakness of the approach.

Similarly, we might point to discussions about deacons and the diaconate, in which deacons had no voice, or discussions about priests and priesthood, in which parish priests had no voice. As mentioned above, two deacons were present at the General Assembly. Yes, there were priests present, but how many were serving as parish priests? The concern is not only that deacons and priests should have the opportunity to be heard, but even more importantly, they are obliged to listen first-hand to the voices around them. Like a choir, the singers must listen to each other. The hope is that as we continue down a synodal path, ways may be found to continue to add voices to the choir. Which is better: to talk about a tenor or to hear one?

The old bishop comes to mind. He came to believe that he had erred by not realizing how the reforms and initiatives of Vatican II would affect the priesthood. The priesthood would remain, he thought, relatively unchanged while everything else around the priest was changing. Only after the Council did he and other bishops realize that their priests were largely unprepared to be the kind of pastoral leaders responsible for implementing the Council’s visions. We might share that concern in the ongoing synodal process. The ministers who will assist in creating and serving in a synodal Church must participate in the formal process so that their voices and experiences can be heard and that they can learn directly from the experiences of others. They have both a right to be heard and an obligation to listen, a responsibility to respond in humility, regarding others as better than themselves, looking not at their own interests, but to the interests of others (Philippians 2:3-4).

Section 11 of the Synthesis Report

Section 11 is composed of three sections: Convergences (4), Issues to Address (2), and Proposals (6).

Convergences

The four “convergences” address the nature and exercise of ordained ministry, an overall positive statement of the diversity and quality of service currently offered by the clergy, a critical concern over clericalism, and finally, how formation leads to an awareness of one’s limitations as well as one’s strengths can help overcome clericalism.

The first point of convergence describes deacons and priests as follows: “The priests are the main cooperators of the Bishop and form a single presbyterate with him; deacons, ordained for the ministry, serve the People of God in the diakonia of the Word, of the liturgy, but above all of charity.”

In general, this sentence is unsurprising. Still, I would observe that the history of the diaconate (especially the patristic record) consistently highlights the unique bond between deacons and their bishop. It is so unique that when a deacon is ordained, only the bishop lays hands on the ordinand, unlike the ordination of presbyters and bishops in which all attending priests lay hands on the new priests and all attending bishops lay hands on the new bishops. The contrast is striking and significant: the deacon has a unique and special relationship with his bishop. Of course, presbyters have their unique priestly fraternity with the bishop, but the omission of the deacon’s relationship with the bishop is unfortunate.

Second, the description of the deacon’s ministry speaks of the three-fold munus of the Word, of the Liturgy, “but above all of charity.” While it is true that charity is characteristic of the deacon and diaconal ministry, it is the “above all” that raises a concern. Pastoral experience and theological analysis since the renewal of the diaconate nearly sixty years ago have developed an understanding that the three munera are to be balanced and integrated. It has been the position of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops that the three functions are inherently interrelated and that no one who is not competent across all three areas is to be ordained. Some theologians have described the relationship of the functions as perichoretic and not simply discrete functions unto themselves. It is commonplace for deacons and their formators to speak of the “three-legged stool” metaphor: if the three legs are unbalanced, the deacon will fall.

The Report also highlights a concern that deacons value and exercise their liturgical and sacramental role at the expense or neglect of charitable service. That, of course, is a reasonable concern. On the other hand, it seems that the very sacramental identity of the deacon is to be found in a balanced exercise of the three-fold munus. One might say it differently: Just as it would be wrong for a deacon to exercise his liturgical function exclusively with no charitable ministry, it would be equally wrong for a deacon to work only in charitable efforts and not take that work into the pulpit or the sanctuary. Over the years of the renewed diaconate, many writers have correctly stressed the balanced exercise of the Word, the Liturgy, and Charity.

The second point of convergence speaks of the diverse forms of pastoral ministry currently exercised by priests and deacons. It is a fine summary, and its description of a synodal approach to ordained ministry is particularly apt. It opens the discussion to the next point of convergence: the dangers of clericalism.

In this third area, clericalism is described as “an obstacle to ministry and mission” and “a deformation of the priesthood.” While the paragraph speaks in general terms of clericalism, I would suggest that all comments focused on priestly formation and attitude toward power over service should be targeted explicitly at all who serve: bishops, presbyters, deacons, religious, and laity.

The fourth and final point of convergence emphasizes “a path of realistic self-knowledge” at all formation levels for ordained ministry. Again, the term associated with Vatican II, co-responsibility, describes the desired approach to ministry, marked by a “style of co-responsibility.” Human formation should help candidates for ordination (deacons and priests) be aware of their human limits as well as their abilities. Notably, the use of language is inclusive of all the ordained and is not restricted to priestly formation. Also significant is the appreciation of the candidate’s family of origin and the community of faith’s role in this process, which has fostered the vocation to ordained ministry.

Issues to Address

Following these four points of convergence, two specific issues are raised. The first is related to the specific formation of deacons and priests for a synodal Church, and the second concerns priestly celibacy for the priests of the Latin Church.

In the United States, the USCCB has issued and revised a series of formation standards for both deacons and priests over several decades. While there are significant similarities in the content of formation (especially in the intellectual dimension), the context of formation for deacons is quite distinct from that of priests. The program for deacon formation is a diocesan responsibility, augmented as possible or necessary by partnerships with Catholic institutes of higher learning. Rather than going away “to the seminary,” deacon formation is conducted in diocesan venues, usually on evenings and weekends, since most deacon candidates are raising families and working in secular careers and professions.

In that regard, then, deacon formation is already “linked to the daily life of the communities.” This is not to suggest that an ongoing review of the overall deacon formation process is unnecessary so as “to avoid the risks of formalism and ideology which lead to authoritarian attitudes.” Both seminary and diocesan formation processes will benefit from the Synod’s call for extensive and creative re-evaluation.

The second issue, concerning priestly celibacy, is straightforward and is a topic that has been long discussed. Does the overall value of celibacy “necessarily translate into a disciplinary obligation in the Latin Church”? While further reflection may be appropriate, it would seem to be an opportune time to move into implementing a program ad experimentum in various locations in which married candidates for presbyteral ordination are admitted to formation and possible ordination to the presbyterate.

Proposals

Six proposals conclude the section. Three of them focus on the diaconate. I will summarize them before commenting on them in globo.

The first proposal recommends an evaluation “of the implementation of the diaconal ministry after the Second Vatican Council,” citing the uneven implementation of the diaconate. Several concerns are mentioned. First, some regions have not introduced it at all. Others fear the diaconate might be misunderstood as an attempted “remedy” for the shortage of priests. Still others were concerned that “sometimes their ministeriality is expressed in the liturgy rather than in service to the poor and needy.” The essential point is sound: implementing a renewed diaconate has been uneven.

Second, the Synod identifies a need “to understand the diaconate first and foremost in itself, and not only as a stage of access to the priesthood.” It points out the linguistic distinction sometimes made between so-called “permanent” and “transitional” deacons as a sign of the failure to describe the diaconate on its own terms. Third, the “uncertainties surrounding the theology of the diaconal ministry” reveal a need for “a more in-depth reflection,” which “will also shed light on the question of women’s access to the diaconate.”

All three proposals have merit and should be pursued enthusiastically, systematically, and comprehensively. However, the language of the proposals suggests that such an evaluation has not been undertaken already in various places. Documents from the Holy See (published in 1998) and from the various episcopal conferences have long cited these areas of concern. The Holy See issued Basic Norms for the Formation of Permanent Deacons jointly with the Directory for the Ministry and Life of Permanent Deacons, which offered significant theological and canonical guidance on the renewal of the diaconate.Almost from the beginning of the 1968 renewal of the diaconate in the United States, the Conference of Bishops has conducted regular assessments on these and related issues.

For example, a significant series of studies by the USCCB in 1995 resulted in the Conference renaming the bishops’ committee responsible for the renewed diaconate to remove the word “Permanent,” changing the Secretariat (and Committee) of the Permanent Diaconate to the Secretariat (and Committee) of the Diaconate in recognition of the theological point that there is one diaconate. Sacramentally, no ordination is “transitional”: once ordained a deacon, one remains a deacon. As I have written elsewhere, we do not refer to a presbyter who later becomes a bishop as a “transitional” priest; he remains a priest. A deacon remains a deacon even if one is later is ordained presbyter or bishop. One practice related to this matter that needs serious review is the continued use of the “apprentice model of the diaconate” of ordaining seminarians to the diaconate before ordination to the presbyterate. This practice continues distorting the possibilities of the diaconate being exercised in a synodal church.

Finally, the USCCB and other episcopal conferences have issued national Directories on deacons’ formation, ministry, and life. In addition to these magisterial efforts, theologians worldwide have studied, taught, and written extensively on these issues.

I enumerate these sources to counter the possible implication of the Synod’s words that the evaluation it is calling for would be something new. Significant pastoral and theological work has been undertaken for decades, and this foundational work could serve well the contemporary synodal call for a “more in-depth evaluation.” Any such new evaluation will have a strong foundation on which to build.

The fourth and fifth proposals implement the previous discussion about the nature and content of clergy formation, including the development of “processes and structures that allow regular verification of the ways in which priests and deacons who carry out roles of responsibility exercise the ministry.” The key would be to have ways for the local community’s involvement in these structures. While these are welcome proposals, one might suggest the feedback and assessment process be expanded to include the episcopate, presbyterate, and diaconate. The final proposal is also straightforward and should be readily implemented, providing an “opportunity to include priests who have left the ministry in a pastoral service that enhances their training and experience.”

Conclusion

Would the presence of additional deacons and priests at the General Assembly have had an impact on any of these and related questions? We cannot know, but one would certainly hope it would have contributed something of value to the process. As synodal strategies are developed and enhanced throughout the Church, deacons and priests will be expected to assist and support the process in concert with everyone else. It is essential that the hearts, hands, and voices of deacons and parish priests be part of the chorus of the faithful now engaged in the discernment of a future synodal Church. If we find ourselves talking about other people rather than talking together with them, we have reached a perilous point. All of us are called to pray, listen, discern, and lend our hearts and hands to build a synodal Church.

Let me state from the outset that this essay is not pointed at any particular political party or candidate in the United States. I write it, not as a political scientist, but as a Catholic deacon who is trying to understand the current state of American political life; consider this a small reflection undertaken as part of my own formation of conscience.

Let me state from the outset that this essay is not pointed at any particular political party or candidate in the United States. I write it, not as a political scientist, but as a Catholic deacon who is trying to understand the current state of American political life; consider this a small reflection undertaken as part of my own formation of conscience.

a paratrooper in the “Band of Brothers” who jumped into France on D-Day, and his letter to his brother following D-Day had a strong impact on all of us. (

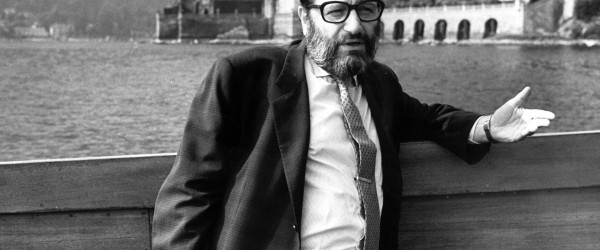

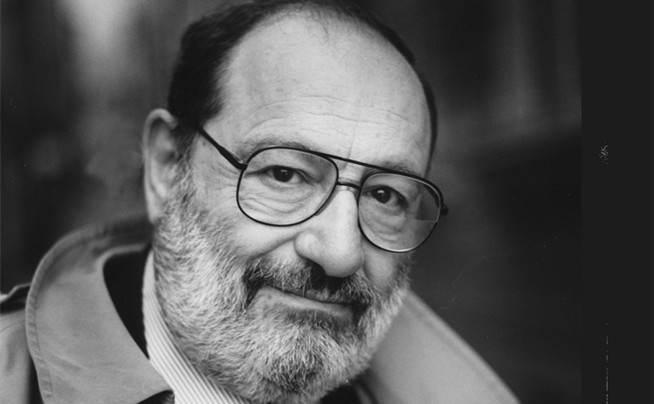

a paratrooper in the “Band of Brothers” who jumped into France on D-Day, and his letter to his brother following D-Day had a strong impact on all of us. ( So it was interesting recently to come across a 1995 essay by Umberto Eco, the great Italian author (The Name of the Rose), scholar and philosopher, entitled “Ur-Fascism.” Written for the New York Review of Books (22 June 1995),

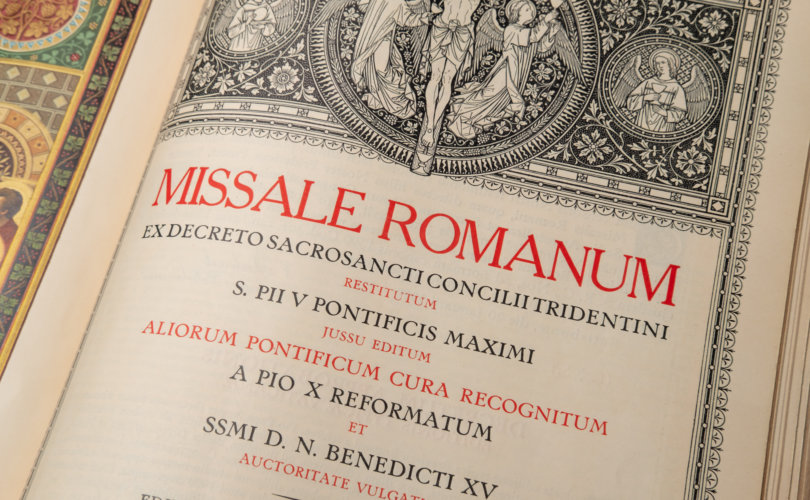

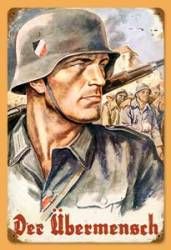

So it was interesting recently to come across a 1995 essay by Umberto Eco, the great Italian author (The Name of the Rose), scholar and philosopher, entitled “Ur-Fascism.” Written for the New York Review of Books (22 June 1995),  Eco points out the first feature of Ur-Fascism is a cult — worship — of tradition. This of course does not deny the importance of tradition itself, as I read him. Rather it is a question of emphasis and loss of balance: when this emphasis on tradition is taken to an extreme that it becomes traditionalism, an extremist point of view. Traditionalism taken to this extreme is found in other times, cultures and systems beside Fascism, of course. In fascist hands, however, traditionalism becomes focused on past glories, past identities, past expressions of truth understood in radical opposition to various forms of rationalism and rationalistic thought. Eco points out that such a response is ancient, reflected in various schools of thought that reacted negatively to classical Greek rationalism. In fact, perhaps the best way to think of this traditionalism that Eco is talking about would be as a kind of Gnosticism. As a result of this worldview, there is no need for new learning, and it reflects an extreme anti-intellectual stance: “Truth has been already spelled out once and for all, and we can only keep interpreting its obscure message,” Eco writes. So, Ur-Fascism would contend mightily with those who suggest that there might be other points of view to consider: this would explain frequent criticism of “intellectual elites” and others who not only seek to uncover the Truth that has existed for all time, but who might also suggest that this Truth might be understood in various ways under differing circumstances. In short, the Fascist says, “We know the Truth, so don’t listen to the ‘intellectual elites’ who will only confuse you.”

Eco points out the first feature of Ur-Fascism is a cult — worship — of tradition. This of course does not deny the importance of tradition itself, as I read him. Rather it is a question of emphasis and loss of balance: when this emphasis on tradition is taken to an extreme that it becomes traditionalism, an extremist point of view. Traditionalism taken to this extreme is found in other times, cultures and systems beside Fascism, of course. In fascist hands, however, traditionalism becomes focused on past glories, past identities, past expressions of truth understood in radical opposition to various forms of rationalism and rationalistic thought. Eco points out that such a response is ancient, reflected in various schools of thought that reacted negatively to classical Greek rationalism. In fact, perhaps the best way to think of this traditionalism that Eco is talking about would be as a kind of Gnosticism. As a result of this worldview, there is no need for new learning, and it reflects an extreme anti-intellectual stance: “Truth has been already spelled out once and for all, and we can only keep interpreting its obscure message,” Eco writes. So, Ur-Fascism would contend mightily with those who suggest that there might be other points of view to consider: this would explain frequent criticism of “intellectual elites” and others who not only seek to uncover the Truth that has existed for all time, but who might also suggest that this Truth might be understood in various ways under differing circumstances. In short, the Fascist says, “We know the Truth, so don’t listen to the ‘intellectual elites’ who will only confuse you.” Such irrationalism is based on what Eco calls “the cult of action for action’s sake”. The fascist sees action as good in itself and therefore action is taken “before, or without” any prior reflection. In the fascist view, thinking is a form of emasculation.

Such irrationalism is based on what Eco calls “the cult of action for action’s sake”. The fascist sees action as good in itself and therefore action is taken “before, or without” any prior reflection. In the fascist view, thinking is a form of emasculation. Yet again, Eco is succinct and on point:

Yet again, Eco is succinct and on point: Certainly, sometimes people are out to get us! Terrorists have made that terribly, tragically, and repeatedly obvious. However, look what Eco points out:

Certainly, sometimes people are out to get us! Terrorists have made that terribly, tragically, and repeatedly obvious. However, look what Eco points out: 9.

9.  10.

10.  14.

14.