INTRODUCTION

Six weeks ago Pope Francis issued an Apostolic Letter called “Traditionis Custodes” (“Guardians of the Tradition”). When I heard the news and read the Letter, my first thought was, “thank God.” In this essay I want to explain why, and suggest several points for moving forward.

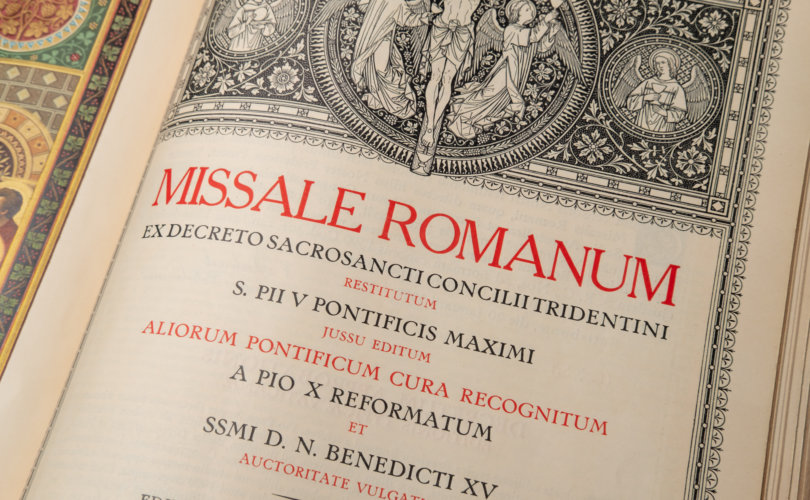

The Letter had little impact on the majority of Catholics, Catholics who celebrate Mass at their local parish, help out as they can, enroll their children in religious education classes, celebrate the sacraments with great joy, and, in short, participate in the life of their parish in peace. However, the Letter exploded like a bomb in the circles of those who refer to themselves as “traditional” or “traditionalist” Catholics. We must be cautious with these terms. All Catholics are “traditional”: we hold that God’s revelation flows from Christ through the double streams of Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. A “traditionalist” has been described as “an advocate of maintaining tradition, especially so as to resist change.” This certainly seems an appropriate characterization of some of these groups. Liturgically, they express this traditionalist identity through the use of the 1962 Missale Romanum and largely reject the principles of liturgical reform mandated made by the Second Vatican Council in its first document, Sacrosanctum Concilium [SC] (the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy), promulgated in December, 1963. With this new Letter and its restrictions on the use of the older form of the Mass, traditionalists are convinced even more that the Catholic Church is headed in the wrong direction.

Historically, liturgical reform began long before Vatican II. But with the affirmation of the reform movement by the Council, and the principles of reform clearly articulated in SC, the pace of liturgical change accelerated. St. Paul VI wasted no time. A month after the promulgation of SC , he instituted the Consilium ad exsequendam Constitutionem de Sacra Liturgia [Council for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy]. Building on the specific principles contained in SC, the Consilium developed the reforms to the Mass, and Pope Paul promulgated the novus ordo Missae (the “new order of the Mass”) in the Roman Missal of 1970. At the end of this essay we will look in detail at his own view of the Roman Missal that bears his name.

PERSONAL TESTIMONY

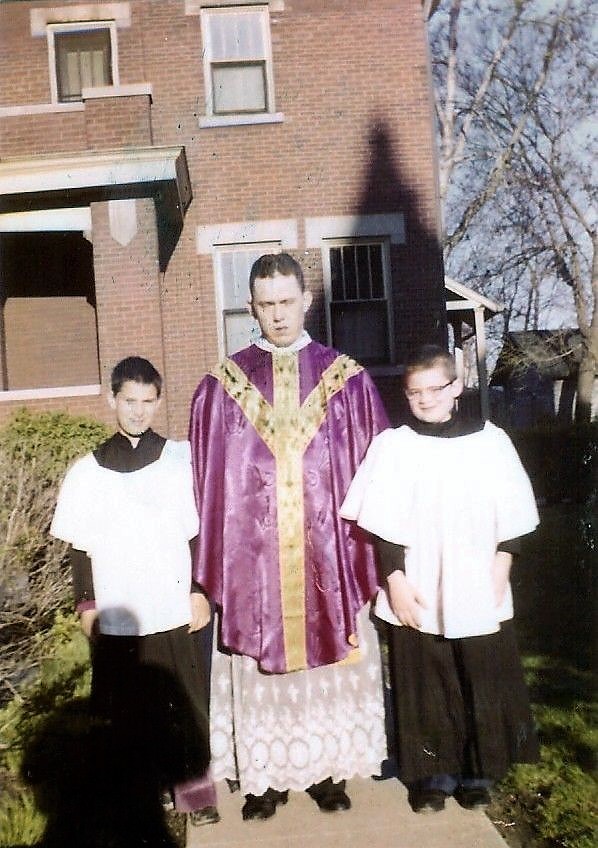

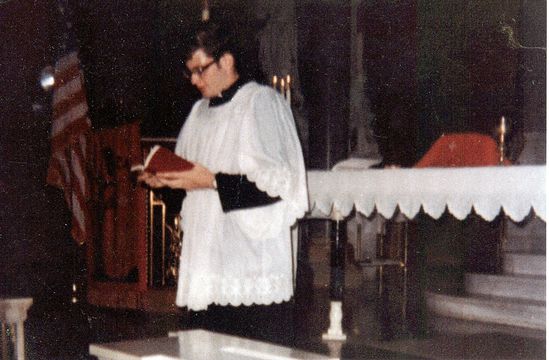

Before going any further, I want to offer some personal testimony from those days. I loved the pre-Conciliar Latin Mass. It was the Mass of my youth. I was born in 1950, and this was the Mass we celebrated every Sunday. When I entered Catholic grade school, it was the Mass we celebrated every day before class. I began serving the Mass in 1957 as a seven year-old third grader. In our parish, we had three Masses on every weekday, and six on Sunday, one of which was a Solemn High Mass. I continued to serve at the parish until I left home in 1963 at age 13 to enter the high school seminary. Obviously, I continued to serve in the seminary, and by age 15 I was Master of Ceremonies for Holy Week when I went home for Easter break. I had also been studying the piano and organ since second grade and by seventh grade, I was one of the three regular organists for our parish, covering all of those Sunday and weekday Masses, along with funerals and weddings. I continued to do this when I would come home for the summers. To say that I was heavily engaged in the liturgical life of the parish would be an understatement. I loved the pre-Conciliar Latin Mass. At the same time, I was enthusiastic about the possibilities of the changes set in motion by the Council.

When I started the seminary, in September, 1963, the Second Vatican Council was entering its second session and, by the time we went home for Christmas vacation that December, Sacrosanctum Concilium had been promulgated by an overwhelming vote by the world’s bishops of 2,147 placet to 4 non placet. By the end of that school year, we were beginning to feel the effects of the changes to come. We were following events in Rome closely. Some of the priests on our faculty had friends and classmates studying and working in Rome, and they would share their own insights about the Council and the discussions taking place among the bishops. The Council was as real to us as if we were actually there. One poignant memory remains with me. During that school year of 1963-64, one of our religion teachers in the seminary was an elderly priest. One day we were talking about the liturgical changes being debated in Rome. Father began to talk about his time as a parish priest, and how special it was to celebrate the Mass for his people. “You know, gentlemen, I am so excited about the possibilities being discussed. For years, I have dreamed of turning around to face my people and say — in English! — ‘The Lord be with you.’ How many times I have turned toward them and said ‘Dominus vobiscum’ to a church of people who had no idea what was going on at the altar.” He continued, “I know that I will never live to see that day, gentlemen, but if — God willing — you become priests, you’ll be able to do just that!” Fortunately, he was wrong. Before the end of that school year, we had received permission from the bishops to implement ad experimentum some of the liturgical changes. There was Father, turning to us with tears in his eyes, greeting us with “The Lord be with you!” I remained in the seminary throughout high school and college (1963-1971), living through the final years of the Council and the first years of its implementation. It was a blessed time.

CURRENT SITUATION

Not everyone accepted the liturgical changes, of course. Various individuals, notably Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, formed groups to celebrate the “old Mass” rather than the “new Mass.” Every pope from Paul VI to Francis has attempted to resolve the disputes with these groups. The goal, of course, is communio. One of the four traditional marks of the Church is the claim that we are “One.” This mark is founded in the priestly prayer of Christ as the Last Supper, when Jesus prayed to His Father “that they may all be one, as you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us” (John 17: 21). Over the decades since the Council, the popes have all showed good faith in working with these groups in a quest to strengthen or in some cases restore that unity.

While I knew some of this history, my research interests revolved around other issues. Since ordination as a deacon for the Archdiocese of Washington, DC, I have served in wide variety of pastoral, diocesan, and national assignments, from Washington, DC, to Iowa, Illinois, and California. In more than three decades of diaconal ministry, I have encountered very few parishioners who characterized themselves as “traditionalist” or who preferred to worship according to the 1962 Missale. So I decided, after the Pope’s letter, that I should look more closely into these matters. My reason was simple: I wanted to see if there was some way to help alleviate the pain these folks were experiencing. I had heard of several popular personalities who had extensive influence on Twitter and YouTube, so off I went.

I began exchanging tweets with one of these personalities, a Texas “influencer” who promptly “blocked” me on Twitter when I suggested some of his claims about the Church were inaccurate. Over on his YouTube channel, one of this man’s “co-hosts” repeatedly mocked “the Novus Ordo Church.” In another video, this same duo condemned, mocked, and dismissed the language they associated with the Council, terms like “pastoral,” “People of God,” and “social justice.” The co-host complained (and, as usual, mocked) Vatican II’s call for a reformed liturgy which involved “the full, conscious, and active participation” of the laity at the Mass. He gleefully reported, to the great amusement of his host, that as a sign of dissent against this teaching, he would pull out his rosary at the “novus ordo” Masses he occasionally and reluctantly attended. Interesting idea: the rosary as dissent! Then I was struck by another fact. While the host repeatedly complained about the constant liturgical “novelties” and “abuses” of the novus ordo, implying widespread experience with the “new Mass,” he remarked casually to his co-host that in all the years since his conversion to Catholicism (he had been a priest in the Episcopal church) he had only attended nine or ten novus ordo Masses!

These commentators are not alone. I spent considerable time looking at other sites to see other reactions to the pope’s Letter. Again, there were hyperbolic, breathless headlines, mostly directed in vitriolic terms against the Holy Father. Not having spent much time in this “traditionalist” world, I was stunned. These people, while claiming an identity of “faithful Catholics,” presented themselves as anything but! To offer any support of Pope Francis was ridiculed as ultramontanism. Furthermore, their mocking dismissal of Vatican II was disturbing. They seemed to lump together all of the world’s bishops who were the Council Fathers of Vatican II, characterizing them as some kind of liberal, hippy, cabal that was out to destroy the Church. Others adopted an attitude that people don’t need to pay attention to Vatican II because it was a “lesser” Council which will go down in history as a minor kerfluffle. Certainly, they say, it was not of the stature of the magnificent Councils of Trent or Nicaea. For the record, all of the twenty-one general Councils of the Church hold the same magisterial status. As I heard and read these comments, I realized that none of these people seemed to have any real substantive knowledge about what the Council was all about: why it was called in the first place, what its goals were, and the vision behind the decisions the world’s bishops made.

Consider again the final vote on Sacrosanctum Concilium. 2,147 bishops approved the text; only 4 disapproved. Look at those numbers. They are incredible. To hear some of our “traditionalist” sisters and brothers, it may seem that there was a huge rift among the bishops about the principles of liturgical reform being promulgated in Sacrosanctum Concilium. There was vigorous debate, of course! However, when the final version was presented for their vote, the bishops were nearly unanimous in their approval.

Fast forward to the present. Pope Francis explained in the Letter that he wrote it after consulting with the bishops of the world and their concerns over the continued usage by some Catholics of the 1962 Missale Romanum. These concerns revolve around the unity and communio of the Church. This was the hope of Pope Benedict when he promulgated Summorum Pontificum. Benedict created a novelty by initiating a practice never before done within a single ritual church. His hope was that by creating two “forms” (the “ordinary” which is the Mass of Paul VI, and the “extraordinary” which is the 1962 Roman Missal) the forms would mutually enrich each other, and those feeling disenfranchised by the liturgical changes following the Council might be reconciled. Unfortunately, despite his good intentions, Benedict’s attempt was a failure. For all their public protestations to the contrary, the “traditionalists” who are “influencers” on social media communicate a radical disunity with the Church and her magisterium. Many of the people I encountered on Twitter and YouTube have come into the Catholic Church from other religious traditions, and it makes one wonder what attracted some of them to the Catholic Church in the first place if they have so many problems with the magisterium of the Church! Nonetheless, I am not judging their motivation, their spirituality, or their love for the Church, and I believe they are attempting to operate in good faith.

Where might we go from here? Consider the following four points.

1) As other commentators have pointed out, this issue is not about Latin. It’s never been about Latin. It is about the Church. It is about ecclesiology. The ancient maxim, dating back as far as the 5th Century St. Prosper of Aquitaine, is lex orandi, lex credendi. How we are praying reflects how we are believing. This goes far beyond the language in which the liturgy is celebrated. If the issue was simply about the use of Latin, that need could be met readily simply by using the Latin editio typica of the current Roman Missal. But this is not about the Latin alone.

What kind of Church is reflected in in the 1962 Missale? And what kind of Church is reflected in the current Missal? As is well known, Vatican II described the Church in scriptural and sacramental terms. The world’s bishops also chose to speak of the Church as a pilgrim and moved away from the previous model of perfectas societas. They also stressed the Trinitarian identity of the entire church in all of its members as the People of God, Mystical Body of Christ, and the Temple of the Holy Spirit. I am not saying that the pre-Conciliar Church did not see itself as sacramental or did not appreciate its Trinitarian foundation. What I am saying is that Vatican II’s vision of Church, as discernible through a study of the historical development of the various drafts of the key conciliar documents, chose to stress aspects of this identity with new focus and emphasis. This can be seen, for example, in many of the changes made to the Mass following the Council. One particular example is that the 1962 Missale refers to the assembly of the faithful at Mass rarely, and these were directions to the priest-celebrant such as to turn toward the people to determine if there were communicants. While much ink has been spilled in the intervening years about what “active participation” by the laity should mean, we must always keep in mind that “active participation” is not to be considered in isolation: Sacrosanctum Concilium almost always links it with “full,” and “conscious.” Consider this passage:

Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that fully conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy. Such participation by the Christian people as “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a redeemed people, is their right and duty by reason of their baptism. In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else; for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit; and therefore pastors of souls must zealously strive to achieve it, by means of the necessary instruction, in all their pastoral work.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, #14

This ecclesiological foundation is behind all of the teaching and action of every Pope since St. Paul VI promulgated the novus ordo missae. The conversation that we should be having is less about Latin or even about which edition of the Mass we should be using. Rather, it must be about the kind of Church we are called to be. One traditionalist commentator is fond of referring dismissively to the post-Conciliar Church as “the Church of Nice,” a Church which doesn’t want to offend anyone, especially those not part of the Catholic Church. It is important to understand that the attitude of the Church’s bishops is born of a desire to respond to Christ’s prayer for unity. One of the goals of the Council and the post-Conciliar papal magisterium has been to work for Christian unity. This does not mean watering down our teachings, but finding areas of common faith and seeking pathways toward ultimate reunion. The Church, according to Vatican II, is to serve “as a leaven and as a kind of soul for human society as it is to be renewed in Christ and transformed into God’s family” (Gaudium et spes, #40).

Reception of Vatican II is, therefore, central to this current issue regarding the Mass. The Council articulated a vision for the future of the Church, and suggested directions for ongoing reform. Vatican II, as all prior twenty general Councils of the Church, articulates magisterial teaching. One does not have the option to say, “I will respect the magisterial authority of THIS Council but not THAT one.” This is a fundamental point being raised by every pope from St. Paul VI to Francis.

2) The normative Roman Missal is not the1962 Missale Romanum. There is discussion among traditionalists that this Missale “was never abrogated” when the 1970 Missal appeared. The traditionalist-vilified novus ordo Missae is the norm, what Benedict XVI termed the “ordinary” form of the Mass. It seems wise to me that the characterization of ordinary and extraordinary forms has been discarded. Given the intimate sacramental relationship between the Eucharist (the Mass) and the Church, such a distinction is not helpful. Remember lex orandi, lex credendi. So, for example, we do not speak of an “ordinary” form of the Church and an “extraordinary” form of the Church. As I said above, the fundamental issue here is not language of the Mass, or the associated rubrics. This is about the Church. The ritual and sui iuris Churches that make up the Catholic Church have one ritual expression of the Eucharist within each Church. The diversity of the Church found in the communion of Catholic Churches is matched by the unity within each Church.

Unfortunately, to read or watch certain certain traditionalist commentators, one would think the situation was reversed: that it was the “new Mass” which is — or should be — the extraordinary form, retaining the 1962 Missale as the ordinary form. In other words, the desire seems to be for a different kind of Church, not simply a different form of the Mass.

3) It was precisely the 1962 Missale that the overwhelming majority of the world’s bishops wanted reformed! This point cannot be overstressed. When the bishops directed a reform of the Mass, the Mass they had in mind was the 1962 Missale. According to the bishops, this Mass needed reform. Again, reading or watching traditionalist commentators, they seem to feel that the unreformed 1962 Missale is perfect as it is and in no need of reform; some would go so far as to say that it cannot be reformed anyway, due to the language of St. Pius V’s Quo Primum, which said no one could ever change the Mass. The simple fact is that, despite the language of Quo Primum, the Mass of Pius V was changed regularly over the centuries , including a new editio typica during the reign of St. John XXIII.

4) Much of the recent agita over Traditionis Custodes has attempted to pit Pope Francis against his immediate predecessor, Pope Benedict. Rather, Pope Francis has as his object the identical positions taken by every Pope from Paul VI onward. It was, in fact, Pope Benedict who tried a novel approach in his well-intentioned but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to heal the breach between those who favor the unreformed 1962 Missale and Catholics who celebrate the reformed Mass of Paul VI. Furthermore, Benedict’s decision to remove diocesan bishops from any role in the use of the “old Mass” in their own dioceses has proven unfortunate and harmful. Pope Francis has now corrected that approach, returning the responsibility of the diocesan bishop as the chief liturgist of his diocese. However, as stressed above, it is critical to remember that both popes share a common vision of Christian unity, following the prayer of Christ. Instead of trying to pit one pope against another, it is far better to find their commonality.

CONCLUSION

On Wednesday, 19 November 1969, St. Pope Paul VI addressed the imminent implementation of the new Roman Missal during his general audience. He anticipated several questions. What follows are direct citations from the address. I include these rather lengthy quotes because of their ongoing applicability.

Question #1: How could such a change be made? Answer: It is due to the will expressed by the Ecumenical Council held not long ago. The Council decreed:

“The rite of the Mass is to be revised in such a way that the intrinsic nature and purpose of its several parts, as also the connection between them, can be more clearly manifested, and that devout and active participation by the faithful can be more easily accomplished. For this purpose the rites are to be simplified, while due care is taken to preserve their substance. Elements which, with the passage of time, came to be duplicated, or were added with but little advantage, are now to be discarded. Where opportunity allows or necessity demands, other elements which have suffered injury through accidents of history are now to be restored to the earlier norm of the Holy Fathers.”

Sacrosanctum Concilium, #50

Pope Paul continues, “The reform which is about to be brought into being is therefore a response to an authoritative mandate from the Church. It is an act of obedience. It is an act of coherence of the Church with herself. It is a step forward for her authentic tradition. . . . It is not an arbitrary act. It is not a transitory or optional experiment. It is not some dilettante’s improvisation. It is a law.”

The pope underscores the unity of the Church, now to be found in its liturgical reform: “This reform puts an end to uncertainties, to discussions, to arbitrary abuses. It calls us back to that uniformity of rites and feeling proper to the Catholic Church, the heir and continuation of that first Christian community, which was all “one single heart and a single soul” (Acts 4:32).

Question #2: What exactly are the changes?

You will see for yourselves that they consist of many new directions for celebrating the rites. . . . But keep this clearly in mind: Nothing has been changed of the substance of our traditional Mass. Perhaps some may allow themselves to be carried away by the impression made by some particular ceremony or additional rubric, and thus think that they conceal some alteration or diminution of truths which were acquired by the Catholic faith for ever, and are sanctioned by it. They might come to believe that the equation between the law of prayer, lex orandi and the law of faith, lex credendi, is compromised as a result.

It is not so. Absolutely not. . . . The Mass of the new rite is and remains the same Mass we have always had. If anything, its sameness has been brought out more clearly in some respects.

The unity of the Lord’s Supper, of the Sacrifice on the cross of the re-presentation and the renewal of both in the Mass, is inviolably affirmed and celebrated in the new rite just as they were in the old. The Mass is and remains the memorial of Christ’s Last Supper. At that Supper the Lord changed the bread and wine into His Body and His Blood, and instituted the Sacrifice of the New Testament. He willed that the Sacrifice should be identically renewed by the power of His Priesthood, conferred on the Apostles. Only the manner of offering is different, namely, an unbloody and sacramental manner; and it is offered in perennial memory of Himself, until His final return (cf. De la Taille, Mysterium Fidei, Elucd. IX).

In the new rite you will find the relationship between the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist, strictly so called, brought out more clearly, as if the latter were the practical response to the former (cf. Bonyer). You will find how much the assembly of the faithful is called upon to participate in the celebration of the Eucharistic sacrifice, and how in the Mass they are and fully feel themselves “the Church.” You will also see other marvelous features of our Mass. But do not think that these things are aimed at altering its genuine and traditional essence.

Rather try to see how the Church desires to give greater efficacy to her liturgical message through this new and more expansive liturgical language; how she wishes to bring home the message to each of her faithful, and to the whole body of the People of God, in a more direct and pastoral way.

Question #3: What will be the results of this innovation? The results expected, or rather desired, are that the faithful will participate in the liturgical mystery with more understanding, in a more practical, a more enjoyable and a more sanctifying way. That is, they will hear the Word of God, which lives and echoes down the centuries and in our individual souls; and they will likewise share in the mystical reality of Christ’s sacramental and propitiatory sacrifice.

The pope concluded, “So do not let us talk about ‘the new Mass.’ Let us rather speak of the ‘new epoch’ in the Church’s life.”

I hope that all of us can take the long view of two centuries of liturgical reform, and see liturgical reform within the even larger revitalization of the Church herself. This is why my first reaction to Traditionis Custodes was to thank God. At Vatican II, the world’s bishops gathered in solemn Council introduced the idea of liturgical reform in just such a way, as part of larger project of ecclesial reform. It is time for all of us — in faithfulness to Scripture, Tradition, and the Magisterium — to set aside fear, the rhetoric of mockery, distortion, and condescension, and recommit ourselves to this vision of the Council:

“This sacred Council has several aims in view: it desires to impart an ever increasing vigor to the Christian life of the faithful; to adapt more suitably to the needs of our own times those institutions which are subject to change; to foster whatever can promote union among all who believe in Christ; to strengthen whatever can help to call the whole of mankind into the household of the Church. The Council therefore sees particularly cogent reasons for undertaking the reform and promotion of the liturgy.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, #1.

This year we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s landmark document on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, which gave added impetus to Catholic participation in the effort. It is also the fiftieth anniversary of the historic meeting between Pope Paul VI and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Athenagoras. Pope John XXIII, from the beginning of his papacy in 1958, had made Christian unity a goal. On 5 June 1960, during the early preparations for the Council, Pope John established a “Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity” as one of the preparatory commissions for the Council, and appointed Cardinal Augustin Bea as its first President. This was the first time that the Holy See had set up an office to deal uniquely with ecumenical affairs.

This year we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s landmark document on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, which gave added impetus to Catholic participation in the effort. It is also the fiftieth anniversary of the historic meeting between Pope Paul VI and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Athenagoras. Pope John XXIII, from the beginning of his papacy in 1958, had made Christian unity a goal. On 5 June 1960, during the early preparations for the Council, Pope John established a “Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity” as one of the preparatory commissions for the Council, and appointed Cardinal Augustin Bea as its first President. This was the first time that the Holy See had set up an office to deal uniquely with ecumenical affairs.