The Catholic blogosphere has been buzzing recently over some comments made by Pope Francis about marriage. Specifically, he remarked that some sacramental marriages are “null” because the bride and groom come from a “culture of the provisional” and do not truly understand the nature of a permanent commitment. Initial reports said that the pope’s original words were that “most” sacramental marriages were null, and then were modified from “most” to “some” or “a part of”. Here’s the original Italian for those who would like to offer their own English translation: “E per questo una parte dei nostri matrimoni sacramentali sono nulli, perché loro [gli sposi] dicono: ‘Sì, per tutta la vita’, ma non sanno quello che dicono, perché hanno un’altra cultura.” You can read the entire address here on the Vatican website.

The Catholic blogosphere has been buzzing recently over some comments made by Pope Francis about marriage. Specifically, he remarked that some sacramental marriages are “null” because the bride and groom come from a “culture of the provisional” and do not truly understand the nature of a permanent commitment. Initial reports said that the pope’s original words were that “most” sacramental marriages were null, and then were modified from “most” to “some” or “a part of”. Here’s the original Italian for those who would like to offer their own English translation: “E per questo una parte dei nostri matrimoni sacramentali sono nulli, perché loro [gli sposi] dicono: ‘Sì, per tutta la vita’, ma non sanno quello che dicono, perché hanno un’altra cultura.” You can read the entire address here on the Vatican website.

The response from certain quarters has been overheated and dramatic. One poor soul on FoxNews has even suggested that the Pope should now resign for these comments! [You can read his assessment here.] What is going on here? Is the ecclesial sky really falling?

I have been reflecting on these opinions and, more important, on the pope latest comments from a pastoral-theological frame of reference (and for the record, I’m NOT saying that a canonical frame of reference is NOT pastoral or theological!). Some initial thoughts:

Pope Francis gestures as he speaks during the opening of the Diocese of Rome’s annual pastoral conference at the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome June 16. Looking on is Cardinal Agostino Vallini, papal vicar for Rome. (CNS photo/Tony Gentile, Reuters)

CONTEXT: I have great respect for many of the canon lawyers who have weighed in on this. They are, for the most part, highly upset for many reasons with the pope’s comments. However, what troubles me in what I’ve been seeing in the blogosphere is a tendency to take the pope out of context; he himself is always cautioning people not to do that with his statements. So, were these latest comments being made to a convention of canonists? Were these comments from an address to the Roman Rota? Were these comments from a lecture being given to canon law students? They were not. Rather, this speech (actually, his words were a response to a question at the end of his speech, so they were not part of his prepared text) was made during the opening of the annual Ecclesial Convocation of the Diocese of Rome, held in the Cathedral for the Diocese of Rome, St. John Lateran. The Pope is, of course, the Bishop of Rome, but he appoints a Cardinal to serve has his Vicar for running the day-to-day operations of the Diocese. At this time, that is Cardinal Agostino Vallini, who served as the host for the opening of this annual event for the Diocese. So, I think the first thing for us to remember is that the pope is speaking here to a gathering of the priests, deacons and other pastoral ministers of his diocesan Church.

POINT OF VIEW: Within this general context, then, I think we need to read the particular comments about marriage within the broader scope of the point he was making. What the Pope was talking about is his recognition and concern with today’s “culture of the provisional” (Italian: E’ la cultura del provvisorio.) In fact, his first example of this culture is not on marriage, but on the priesthood. The pope recounts the story of a young man who expressed interest in serving as a priest, but only for a period of ten years! His primary concern here is to express how an overarching culture of the provisional impacts every state of life today, including the priesthood, religious life and matrimony. It is for this reason that he then makes his statement that many sacramental marriages today are null.

This is certainly not a new theme for Pope Francis. Here are just a few random links to earlier comments which make the same point, but without the use of the term “null”: here, here, and here.

It seems pretty clear and straightforward that, whether the pope originally said “most” or “some” marriages is pastorally irrelevant to the point he’s trying to make: that because we are now living in such a culture of the provisional, everyone struggles with the ability to make lifelong commitments; on one level, they may think they understand the nature of permanence, but on another level, they may be incapable of making such a judgment. The pope is not speaking here as the Legislator or as a judge in a marriage tribunal: he’s speaking from the perspective of an experienced pastor.

It seems pretty clear and straightforward that, whether the pope originally said “most” or “some” marriages is pastorally irrelevant to the point he’s trying to make: that because we are now living in such a culture of the provisional, everyone struggles with the ability to make lifelong commitments; on one level, they may think they understand the nature of permanence, but on another level, they may be incapable of making such a judgment. The pope is not speaking here as the Legislator or as a judge in a marriage tribunal: he’s speaking from the perspective of an experienced pastor.

He’s actually saying what most ministers readily admit: that most people today have lost a sense of the permanent and that it is hard to find anyone who is willing or able to make a long-term commitment to anything or anyone. One retired pastor, when I mentioned this kerfuffle to him, replied, “The Pope didn’t say anything that most bishops, priests and deacons who work with engaged couples don’t already acknowledge.” The pope was simply telling his diocesan pastoral ministers that they need to do what they can to help ALL of their people come to a greater sense of permanent commitment: to their faith in general, to their vocational aspirations, and so on. In my opinion, to read his words and then to jump immediately to canonical judgments about those statements risks losing the BIG PICTURE of what the pope was saying.

The bottom line, it seems to me, is pretty straightforward: The first step in listening to the pope is to look at the overall message he is trying to make and to whom he is making it. Generally speaking, with Pope Francis, he chooses to speak as who he is: a pastor. He does not speak as an academic theologian, or as a canon lawyer, nor should he, in my opinion. He is first, foremost and always, a Pastor: that’s his frame of reference, that’s his motivation, that’s his primary concern. Theology, canon law, curial structures, and all the rest of the ad intra organs of the Catholic Church exist to SUPPORT that pastoral effort. We all look at the world through the lenses we’ve been given in life: as teachers, as lawyers, doctors, farmers, business people, parents, and even deacons. For some canon lawyers to be upset and concerned by the pope’s comments is only natural, but they should not be considered the first — or only — line in interpretation of papal statements.

The bottom line, it seems to me, is pretty straightforward: The first step in listening to the pope is to look at the overall message he is trying to make and to whom he is making it. Generally speaking, with Pope Francis, he chooses to speak as who he is: a pastor. He does not speak as an academic theologian, or as a canon lawyer, nor should he, in my opinion. He is first, foremost and always, a Pastor: that’s his frame of reference, that’s his motivation, that’s his primary concern. Theology, canon law, curial structures, and all the rest of the ad intra organs of the Catholic Church exist to SUPPORT that pastoral effort. We all look at the world through the lenses we’ve been given in life: as teachers, as lawyers, doctors, farmers, business people, parents, and even deacons. For some canon lawyers to be upset and concerned by the pope’s comments is only natural, but they should not be considered the first — or only — line in interpretation of papal statements.

I think, for those of us who serve as deacons, our take away from all of this might best be: how can I help the couples with whom I’m working come to a greater appreciation and understanding of the permanence of our beautiful sacrament of Matrimony?

The Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy focused over the last few days on the ministry of deacons. Today the Holy Father celebrated Mass in Saint Peter’s Square and thousands of the world’s deacons were there. The Holy Father’s homily is a short but powerful lesson in diakonia.

The Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy focused over the last few days on the ministry of deacons. Today the Holy Father celebrated Mass in Saint Peter’s Square and thousands of the world’s deacons were there. The Holy Father’s homily is a short but powerful lesson in diakonia.

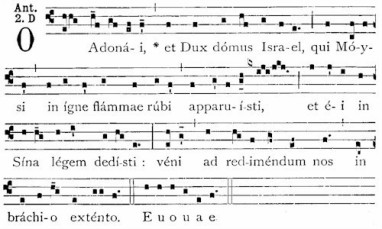

The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived.

The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived. God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on:

Today in Rome the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with Jews released a new document exploring unresolved theological questions at the heart of Christian-Jewish dialogue. According to Vatican Radio,

Today in Rome the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with Jews released a new document exploring unresolved theological questions at the heart of Christian-Jewish dialogue. According to Vatican Radio, It has been a distinct privilege for me over the years to serve as a Hebrew linguist in a variety of contexts, and five years ago I was asked by the Center for Catholic-Jewish Studies to give a very brief reflection on “The Significance of Nostra Aetate” on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of its promulgation by the Second Vatican Council. So what I am about to write should not be read in any way as a criticism of the great efforts that have been made over the past fifty years to celebrate the relationship of Jews and Catholics! And, as the new document released today underscores, so much more remains to be done in this regard, and I fully embrace that effort.

It has been a distinct privilege for me over the years to serve as a Hebrew linguist in a variety of contexts, and five years ago I was asked by the Center for Catholic-Jewish Studies to give a very brief reflection on “The Significance of Nostra Aetate” on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of its promulgation by the Second Vatican Council. So what I am about to write should not be read in any way as a criticism of the great efforts that have been made over the past fifty years to celebrate the relationship of Jews and Catholics! And, as the new document released today underscores, so much more remains to be done in this regard, and I fully embrace that effort. Let’s take a closer look at the document itself. Much has been written about the genesis of the document, so there is no need to rehearse all of that here. Suffice it to say that Nostra Aetate, in the final analysis, is not the work of one person, as influential as so many individuals were in its inception and development: John XXIII himself, Jules Isaac, Augustin Bea, to name just a few.

Let’s take a closer look at the document itself. Much has been written about the genesis of the document, so there is no need to rehearse all of that here. Suffice it to say that Nostra Aetate, in the final analysis, is not the work of one person, as influential as so many individuals were in its inception and development: John XXIII himself, Jules Isaac, Augustin Bea, to name just a few. The reason that Pope John called the Council in the first place was so that all the bishops from around the world could together tackle the very real life and death issues that were affecting all people, not just Catholics. This was not some simple superficial ceremonial event; it was, in fact, an attempt to make faith in God something transformative so that the world would never again find itself in the midst of the tragedies of the first half of the 20th century. It is in this light, then, that the significance of Nostra Aetate must be seen.

The reason that Pope John called the Council in the first place was so that all the bishops from around the world could together tackle the very real life and death issues that were affecting all people, not just Catholics. This was not some simple superficial ceremonial event; it was, in fact, an attempt to make faith in God something transformative so that the world would never again find itself in the midst of the tragedies of the first half of the 20th century. It is in this light, then, that the significance of Nostra Aetate must be seen. So far, then, the Council is focused on all people. Now, in paragraph #2 the bishops turn to people who have found “a certain perception of that hidden power which hovers over the course of things and over the events of human history; at times some indeed have come to the recognition of a Supreme Being, or even of a Father. This perception and recognition penetrates their lives with a profound religious sense.” These comments apply to a wide variety of religious expression, from various Eastern forms to Native American and on and on. Then they turn specifically to certain Eastern religions:

So far, then, the Council is focused on all people. Now, in paragraph #2 the bishops turn to people who have found “a certain perception of that hidden power which hovers over the course of things and over the events of human history; at times some indeed have come to the recognition of a Supreme Being, or even of a Father. This perception and recognition penetrates their lives with a profound religious sense.” These comments apply to a wide variety of religious expression, from various Eastern forms to Native American and on and on. Then they turn specifically to certain Eastern religions: Buddhism, in its various forms, realizes the radical insufficiency of this changeable world; it teaches a way by which people, in a devout and confident spirit, may be able either to acquire the state of perfect liberation, or attain, by their own efforts or through higher help, supreme illumination.

Buddhism, in its various forms, realizes the radical insufficiency of this changeable world; it teaches a way by which people, in a devout and confident spirit, may be able either to acquire the state of perfect liberation, or attain, by their own efforts or through higher help, supreme illumination. Paragraph #3 specifically addresses Islam:

Paragraph #3 specifically addresses Islam: And in language made even more poignant over the last generation, the bishops write:

And in language made even more poignant over the last generation, the bishops write:

The Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy, proclaimed by Pope Francis today in Rome, actually began fifty years ago with the solemn closing of the Second Vatican Council on 8 December 1965. When dealing with the Catholic Church it is always good to step back and take a long view on what is going on, and today’s events in Rome are no exception. Let’s connect some dots.

The Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy, proclaimed by Pope Francis today in Rome, actually began fifty years ago with the solemn closing of the Second Vatican Council on 8 December 1965. When dealing with the Catholic Church it is always good to step back and take a long view on what is going on, and today’s events in Rome are no exception. Let’s connect some dots. The Church’s teaching about Mary was originally crafted as a separate document by the curia before the Council began. However, the world’s bishops rejected this arrangement, rightly including Mary at the heart and climax of its dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen gentium. Mary, our sister and our mother, the first disciple of the Christ, is held up to all as the model of Christian discipleship. Fifty years ago, therefore, standing on the same spot where Pope Francis stood earlier this morning, Pope Paul VI ended his homily with the following observation:

The Church’s teaching about Mary was originally crafted as a separate document by the curia before the Council began. However, the world’s bishops rejected this arrangement, rightly including Mary at the heart and climax of its dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen gentium. Mary, our sister and our mother, the first disciple of the Christ, is held up to all as the model of Christian discipleship. Fifty years ago, therefore, standing on the same spot where Pope Francis stood earlier this morning, Pope Paul VI ended his homily with the following observation: Vatican II is a gift that keeps on giving. The great historian of the Church, Hubert Jedin, once observed that it takes at least a century to implement the teachings and decisions of a general Council. If he is correct, and I believe he is, we have only now just reached the fifty yard line as we say in American football. For all the progress made, much more remains to be done. Let’s take a closer look at those closing ceremonies to the Council, because there are some significant elements there that point the way to what happened earlier today.

Vatican II is a gift that keeps on giving. The great historian of the Church, Hubert Jedin, once observed that it takes at least a century to implement the teachings and decisions of a general Council. If he is correct, and I believe he is, we have only now just reached the fifty yard line as we say in American football. For all the progress made, much more remains to be done. Let’s take a closer look at those closing ceremonies to the Council, because there are some significant elements there that point the way to what happened earlier today. Another point we must stress is this: all this rich teaching is channeled in one direction, the service of mankind, of every condition, in every weakness and need. The Church has, so to say, declared herself the servant of humanity, at the very time when her teaching role and her pastoral government have, by reason of the council’s solemnity, assumed greater splendor and vigor: the idea of service has been central.

Another point we must stress is this: all this rich teaching is channeled in one direction, the service of mankind, of every condition, in every weakness and need. The Church has, so to say, declared herself the servant of humanity, at the very time when her teaching role and her pastoral government have, by reason of the council’s solemnity, assumed greater splendor and vigor: the idea of service has been central. Pope Paul digs deeper, using the image of a bell:

Pope Paul digs deeper, using the image of a bell: Finally, at the end of the Mass closing the Council, a remarkable thing happened. Most people today are unaware that it even took place, and that is a real tragedy, for it sheds a light on the whole proceedings, and points the way to our contemporary Jubilee. A series of messages from the Council Fathers was read to the world. The bishops of the Council prepared these messages because they wanted the world to realize that the Council had not been simply an exercise of ecclesiastical navel-gazing; rather, the work of the Council was focused outward, to the very real needs of the people and the world. In the introduction to the messages, the bishops write:

Finally, at the end of the Mass closing the Council, a remarkable thing happened. Most people today are unaware that it even took place, and that is a real tragedy, for it sheds a light on the whole proceedings, and points the way to our contemporary Jubilee. A series of messages from the Council Fathers was read to the world. The bishops of the Council prepared these messages because they wanted the world to realize that the Council had not been simply an exercise of ecclesiastical navel-gazing; rather, the work of the Council was focused outward, to the very real needs of the people and the world. In the introduction to the messages, the bishops write: Today, here in Rome and in all the dioceses of the world, as we pass through the Holy Door, we also want to remember another door, which fifty years ago the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council opened to the world. This anniversary cannot be remembered only for the legacy of the Council’s documents, which testify to a great advance in faith. Before all else the Council was an encounter. A genuine encounter between the Church and the men and women of our time. An encounter marked by the power of the Spirit, who impelled the Church to emerge from the shoals which for years had kept her self-enclosed so as to set out once again, with enthusiasm, on her missionary journey. . . Wherever there are people, the Church is called to reach out to them and to bring the joy of the Gospel, ,and the mercy and forgiveness of God. After these decades, we again take up this missionary drive with the same power and enthusiasm. The Jubilee challenges us to this openness, and demands that we not neglect the spirit which emerged from Vatican II, the spirit of the Samaritan, as Blessed Paul VI expressed it at the conclusion of the Council. May our passing through the Holy Door today commit us to making our own the mercy of the Good Samaritan.

Today, here in Rome and in all the dioceses of the world, as we pass through the Holy Door, we also want to remember another door, which fifty years ago the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council opened to the world. This anniversary cannot be remembered only for the legacy of the Council’s documents, which testify to a great advance in faith. Before all else the Council was an encounter. A genuine encounter between the Church and the men and women of our time. An encounter marked by the power of the Spirit, who impelled the Church to emerge from the shoals which for years had kept her self-enclosed so as to set out once again, with enthusiasm, on her missionary journey. . . Wherever there are people, the Church is called to reach out to them and to bring the joy of the Gospel, ,and the mercy and forgiveness of God. After these decades, we again take up this missionary drive with the same power and enthusiasm. The Jubilee challenges us to this openness, and demands that we not neglect the spirit which emerged from Vatican II, the spirit of the Samaritan, as Blessed Paul VI expressed it at the conclusion of the Council. May our passing through the Holy Door today commit us to making our own the mercy of the Good Samaritan.