INTRODUCTION

Jesuit Father Thomas Reese has, once again, wheeled out some tired old myths and misperceptions about the diaconate. He seems to go through this exercise every so often. His argument seems to be that if the Church starts to ordain women as deacons, all will be well. However, if the Church doesn’t ordain women deacons, then no one should be ordained deacons. He seems to say that the diaconate is sacramental and necessary if women are ordained, but not sacramental or necessary if they are not. He reaches this bizarre conclusion applying principles that are ahistorical, theologically untenable, and downright dangerous in their ignorance of the matters involved. Such misinformation must be addressed.

As I say, Father Reese has done all this before. I responded to him before on this blog, and I will copy it again here for the reader’s convenience. Here it is:

==============================

DEACONS: MYTHS AND MISPERCEPTIONS

Jesuit Father Thomas Reese has published an interesting piece over at NCRonline entitled “Women Deacons? Yes. Deacons? Maybe.” I have a lot of respect for Fr. Tom, and I thank him for taking the time to highlight the diaconate at this most interesting time. As the apostolic Commission prepares to assemble to discuss the question of the history of women in diaconal ministry, it is good for all to remember that none of this is happening in a vacuum. IF women are eventually ordained as deacons in the contemporary Church, then they will be joining an Order of ministry that has developed much over the last fifty years. Consider one simple fact: In January 1967 there were zero (0) “permanent” deacons in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church (the last two lived and died in the 19th Century). Today there are well over 40,000 deacons serving worldwide. By any numerical measure, this has to be seen as one of the great success stories of the Second Vatican Council. Over the last fifty years, then, the Church has learned much about the nature of this renewed order, its exercise, formation, assignment and utilization. The current question, therefore, rests upon a foundation of considerable depth, while admitting that much more needs to be done.

However, Father Reese’s column rests on some commonly-held misperceptions and errors of fact regarding the renewal of the diaconate. Since these errors are often repeated without challenge or correction, I think we need to make sure this foundation is solid lest we build a building that is doomed to fall down. So, I will address some of these fault lines in the order presented:

- The“Disappearance” of Male Deacons

Father states that “[Women deacons] disappeared in the West around the same time as male deacons.” On the contrary, male deacons remained a distinct order of ministry (and one not automatically destined for the presbyterate) until at least the 9th Century in the West. This is attested to by a variety of sources. Certainly, throughout these centuries, many deacons — the prime assistants to bishops — were elected to succeed their bishops. Later in this period, as the Roman cursus honorum took hold more definitively, deacons were often ordained to the presbyterate, leading to what is incorrectly referred to as the “transitional” diaconate. However, both in a “permanent” sense and a “transitional” sense, male deacons never disappeared.

- The Renewal of Diaconate as Third World Proposal

Father Tom writes that his hesitancy concerning the diaconate itself “is not with women deacons, but with the whole idea of deacons as currently practiced in the United States.” (I would suggest that this narrow focus misses the richness of the diaconate worldwide.) He then turns to the Council to provide a foundation for what follows. He writes, “The renewal of the diaconate was proposed at the Second Vatican Council as a solution to the shortage of native priests in missionary territories. In fact, the bishops of Africa said, no thank you. They preferred to use lay catechists rather than deacons.” This statement simply is not true and does not reflect the history leading up to the Council or the discussions that took place during the Council on the question of the diaconate.

As I and others have written extensively, the origins of the contemporary diaconate lie in the early 19th Century, especially in Germany and France. In fact there is considerable linkage between the early liturgical movement (such as the Benedictine liturgical reforms at Solesmes) and the early discussions about a renewed diaconate: both stemmed from a desire to increase participation of the faithful in the life of the Church, both at liturgy and in life. In Germany, frequent allusion was made to the gulf that existed between priests and bishops and their people. Deacons were discussed as early as 1840 as a possible way to reconnect people with their pastoral leadership. This discussion continued throughout the 19th Century and into the 20th. It became a common topic of the Deutschercaritasberband (the German Caritas organization) before and during the early years of the Nazi regime, and it would recur in the conversations held by priest-prisoners in Dachau. Following the war, these survivors wrote articles and books on the need for a renewed diaconate — NOT because of a priest shortage, but because of a desire to present a more complete image of Christ to the world: not only Christ the High Priest, but the kenotic Christ the Servant as well. As Father Joseph Komonchak famously quipped, “Vatican II did not restore the diaconate because of a shortage of priests but because of a shortage of deacons.”

Certainly, there was some modest interest in this question by missionary bishops before the Council. But it remained largely a European proposal. Consider some statistics. During the antepreparatory stage leading up to the Council (1960-1961), during which time close to 9,000 proposals were presented from the world’s bishops, deans of schools of theology, and heads of men’s religious congregations, 101 proposals concerned the possible renewal of the diaconate. Eleven of these proposals were against the idea of having the diaconate (either as a transitional or as a permanent order), while 90 were in favor of a renewed, stable (“permanent”) diaconate. Nearly 500 bishops from around the world supported some form of these 90 proposals, with only about 100 of them from Latin America and Africa. Nearly 400 bishops, almost entirely from both Western and Eastern Europe, were the principal proponents of a renewed diaconate (by the way, the bishops of the United States, who had not had the benefit of the century-long conversation about the diaconate, were largely silent on the matter, and the handful who spoke were generally against the idea). Notice how these statistics relate to Father Tom’s observation. First, the renewed diaconate was largely a European proposal, not surprising given the history I’ve outlined above. Second, notice that despite this fact, it is also wrong to say that “the African bishops said no thank you” to the idea. Large numbers of them wanted a renewed diaconate, and even today, the diaconate has been renewed in a growing number of African dioceses.

One other observation on this point needs to be made. No bishop whose diocese is suffering from a shortage of priests would suggest that deacons would be a suitable strategy. After all, as we all know, deacons do not celebrate Mass, hear confessions or anoint the sick. If a diocese needed more priests, they would not have turned to the diaconate. Yes, there was some discussion at the Council that deacons could be of assistance to priests, but the presumption was that there were already priests to hand.

In short, the myth that “the diaconate was a third world initiative due to a shortage of priests” simply has never held up, despite its longstanding popularity.

- Deacons as Part-Time Ministers

Father cites national statistics that point out that deacons are largely unpaid, “most of whom make a living doing secular work.” “Why,” he asks, “are we ordaining part-time ministers and not full-time ministers?”

Let’s break this down. First, there never has been, nor will there ever be, a “part-time deacon.” We’re all full-time ministers. Here’s the problem: Because the Catholic Church did not have the advantage of the extensive conversation on diaconate that was held in other parts of the world, we have not fully accepted the notion that ministry extends BEYOND the boundaries of the institutional church itself. Some of the rationale behind the renewal of the diaconate in the 19th Century and forward has been to place the Church’s sacred ministers in places where the clergy had previously not been able to go! Consider the “worker-priest” movement in France. This was based on a similar desire to extend the reach of the Church’s official ministry outside of the parish and outside of the sanctuary. However, if we can only envision “ministry” as something that takes place within the sanctuary or within the parish, then we miss a huge point of the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and, I would suggest, the papal magisterium of Pope Francis. The point of the diaconate is to extend the reach of the bishop into places the bishop can’t normally be present. That means that no matter what the deacon is doing, no matter where the deacon is working or serving, the deacon is ministering to those around him.

We seem to understand this when we speak about priests, but not about deacons. When a priest is serving in some specialized work such as president of a university, or teaching history or social studies or science at a high school, we would never suggest that he is a “part-time” minister. Rather, we would correctly say that it is ALL ministry. Deacons take that even further, ministering in our various workplaces and professions. It was exactly this kind of societal and cultural leavening that the Council desired with regard to the laity and to the ordained ministry of the deacon. The bottom line is that we have to expand our view of what we mean by the term “ministry”!

- “Laypersons can do everything a deacon can do“

Father writes, “But the truth is that a layperson can do everything that a deacon can do.” He then offers some examples. Not so fast.

Not unlike the previous point, this is a common misperception. However, it is only made if one reduces “being a deacon” to the functions one performs. Let’s ponder that a moment. We live in a sacramental Church. This means that there’s more to things than outward appearances. Consider the sacrament of matrimony. Those of us who are married know that there is much, much more to “being married” than simply the sum of the functions associated with marriage. Those who are priests or bishops know that there is more to who they are as priests and bishops than simply the sum of what they do. So, why can’t they see that about deacons? There is more to “being deacon” than simply the sum of what we do. And, frankly, do we want priests to stop visiting the sick in hospitals or the incarcerated in prisons simply because a lay person can (and should!) be doing that? Shall we have Father stop being a college professor because now we have lay people who can do that? Shall we simply reduce Father to the sacraments over which he presides? What a sacramentally arid Church we would become!

The fact is, there IS a difference when a person does something as an ordained person. Thomas Aquinas observed that an ordained person acts in persona Christi et in nomine Ecclesiae — in the person of Christ and in the name of the Church. There is a public and permanent dimension to all ordained ministry that provides the sacramental foundation for all that we try to do in the name of the Church. We are more than the sum of our parts, we are more than the sum of our functions.

- “We have deacons. . . because they get more respect”

With all respect to a man I deeply admire, I expect that most deacons who read this part of the column are still chuckling. Yes, I have been treated with great respect by most of the people with whom I’ve served, including laity, religious, priests and bishops. On the other hand, the experience of most deacons does not sustain Father’s observation. The fact is, most people, especially if they’re not used to the ministry of deacons, don’t associate deacons with ordination. I can’t tell the number of times that I’ve been asked by someone, “When will you be ordained?” — meaning ordination to the priesthood. They know I am a deacon, but, as some people will say, “but that one really doesn’t count, does it?” I had another priest once tell me, “Being a deacon isn’t a real vocation like the priesthood.” If it’s respect a person is after “beyond their competence” (to quote Father Reese), then it’s best to avoid the diaconate.

No, the truth is that we have deacons because the Church herself is called to be deacon to the world (cf. Paul VI). Just as we are a priestly people who nonetheless have ministerial priests to help us actualize our priestly identity, so too we have ministerial deacons to help us actualize our ecclesial identity as servants to and in the world. To suggest that we have deacons simply because of issues of “respect” simply misses the point of 150 years of theological and pastoral reflection on the nature of the Church and on the diaconate.

In all sincerity, I thank Father Reese for his column on the diaconate, and I look forward to the ongoing conversation about this exciting renewed order of ministry of our Church.

=================================

CONCLUSION

I ended that earlier article with the hope of an ongoing conversation with Father Reese about the diaconate. Unfortunately, it seems that will not be happening. Father seems stuck in the mire of myths and misperceptions that have long been debunked by historical fact, theological development, and, in the final analysis, the lived pastoral experience of the Church and the Church’s deacons over the nearly six decades of the renewal of the diaconate. In the name of the Church, deacons are ordained to “animate the Church’s service” (St. Pope Paul VI) and to be “the Church’s service sacramentalized” (Pope St. John Paul II).

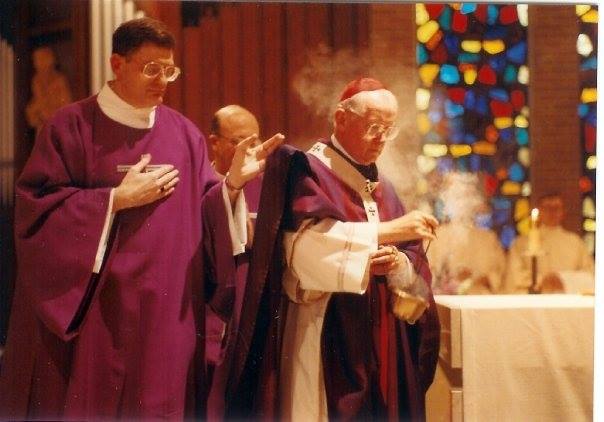

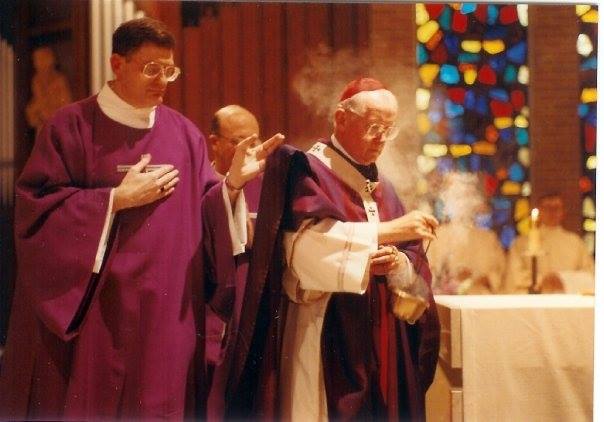

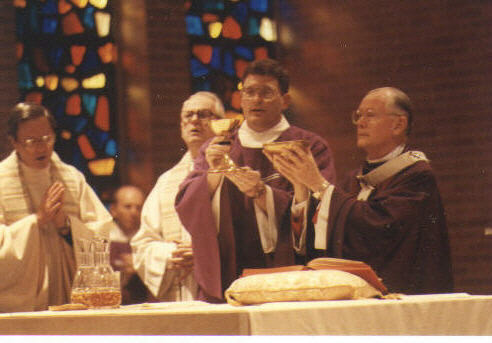

This Sunday, 25 March 2018, is Palm Sunday. But 28 years ago, it was the Fourth Sunday of Lent (Laetare Sunday) — and on that date I was ordained a deacon of the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Washington, DC by our Cardinal-Archbishop, James A. Hickey.

This Sunday, 25 March 2018, is Palm Sunday. But 28 years ago, it was the Fourth Sunday of Lent (Laetare Sunday) — and on that date I was ordained a deacon of the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Washington, DC by our Cardinal-Archbishop, James A. Hickey. At that time I was a Commander in the United States Navy, under orders to report to the US Naval Security Group Activity, Hanza, Okinawa, Japan as Executive Officer. For the previous three years, while assigned to the National Security Agency, I had participated in the deacon formation program of the Archdiocese of Washington, DC. When my orders to Okinawa arrived, I contacted Deacon Tom Knestout, our deacon director, and then-Father Bill Lori, priest-secretary to Cardinal James Hickey (and now the Archbishop of Baltimore). Father Lori, God bless him, jumped to the meat of the issue, “Shall we ask the Cardinal to ordain you early, before you leave?” Within 10 minutes, the Cardinal had approved the request and the date was set.

At that time I was a Commander in the United States Navy, under orders to report to the US Naval Security Group Activity, Hanza, Okinawa, Japan as Executive Officer. For the previous three years, while assigned to the National Security Agency, I had participated in the deacon formation program of the Archdiocese of Washington, DC. When my orders to Okinawa arrived, I contacted Deacon Tom Knestout, our deacon director, and then-Father Bill Lori, priest-secretary to Cardinal James Hickey (and now the Archbishop of Baltimore). Father Lori, God bless him, jumped to the meat of the issue, “Shall we ask the Cardinal to ordain you early, before you leave?” Within 10 minutes, the Cardinal had approved the request and the date was set. To see families, large and small, approaching the font, is an inexpressible joy.) Twenty-eight years ago, I could not have imagined the journey to come; I suppose we can all say that about our lives!

To see families, large and small, approaching the font, is an inexpressible joy.) Twenty-eight years ago, I could not have imagined the journey to come; I suppose we can all say that about our lives!