It’s Lent: a time for purification and enlightenment, according to the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. Most of us grew up thinking of Lent in terms of what we were going to “give up.” Speaking only for myself, I sometimes wish I could give up following what passes these days for American political “discourse.” But as Pope Francis said recently, quoting Aristotle, a human being is by nature a “political animal.” We cannot and should not avoid the political process; in fact, we have a moral obligation to participate to the best of our abilities! As Catholics, then, how might we participate in ways consistent with Christian discipleship? For those of us who also serve as Catholic clergy, what are our own obligations and limitations with regard to political life?

It’s Lent: a time for purification and enlightenment, according to the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. Most of us grew up thinking of Lent in terms of what we were going to “give up.” Speaking only for myself, I sometimes wish I could give up following what passes these days for American political “discourse.” But as Pope Francis said recently, quoting Aristotle, a human being is by nature a “political animal.” We cannot and should not avoid the political process; in fact, we have a moral obligation to participate to the best of our abilities! As Catholics, then, how might we participate in ways consistent with Christian discipleship? For those of us who also serve as Catholic clergy, what are our own obligations and limitations with regard to political life?

American political life has always been, to say the least, exciting, interesting, and inherently disputatious: there’s nothing new about that. Consider just a few historic, pointed quotes from Mark Twain (1835-1910) and Will Rogers (1879-1935):

American political life has always been, to say the least, exciting, interesting, and inherently disputatious: there’s nothing new about that. Consider just a few historic, pointed quotes from Mark Twain (1835-1910) and Will Rogers (1879-1935):

Here’s Mark Twain, writing about politics in the 19th Century:

The political and commercial morals of the United States are not merely food for laughter, they are an entire banquet.

Never argue with stupid people. They will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.

A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.

Patriot: the person who can holler the loudest without knowing what he is hollering about.

Anger is an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.

A half-truth is the most cowardly of lies.

And here’s Will Rogers with some observations about American politics during the 1920’s an 1930’s:

And here’s Will Rogers with some observations about American politics during the 1920’s an 1930’s:

There is only one redeeming thing about this whole election. It will be over at sundown, and let everybody pray that it’s not a tie, for we couldn’t go through with this thing again.

If you ever injected truth into politics you have no politics.

This country has gotten where it is in spite of politics, not by the aid of it. That we have carried as much political bunk as we have and still survived shows we are a super nation.

America has the best politicians money can buy.

The Senate just sits and waits till they find out what the president wants, so they know how to vote against him.

A president just can’t make much showing against congress. They lay awake nights, thinking up things to be against the president on.

There’s no trick to being a humorist when you have the entire government working for you.

Politics is a great character builder. You have to take a referendum to see what your convictions are for that day.

Today, however, I think most people would readily admit that what passes for political “discourse” has deteriorated to a level that does not warrant the term, since “discourse” is supposed to be “a communication of thought by words, talk, or conversation; earnest and intelligent exchange” or “a formal discussion of a subject in speech or writing. . . .”

Gregory M. Aymond, the Archbishop of New Orleans, has written an excellent column, “What has happened to civility in politics?” (read the whole piece here) in which he observes,

Gregory M. Aymond, the Archbishop of New Orleans, has written an excellent column, “What has happened to civility in politics?” (read the whole piece here) in which he observes,

What has happened to politics, from my perspective, is candidates in campaigns no longer run on merit, their qualifications or their ability to lead, but run on the weaknesses of the other person. The name-calling and insulting comments that candidates exchange, in my mind, create an evil spirit among us.

Archbishop Aymond outlines four principles for evaluating a political candidate:

- Human Life: This principle covers the spectrum from conception to natural death, with the Archbishop listing abortion, euthanasia, the death penalty, caring for the poor, issues regarding biotechnology, issues of war and the promotion of peace “in our country and beyond.”

- Family Life: This principle obviously includes marriage, and “a candidate must be willing to do all he or she can to help a person form a family that gives respect to family and children.” This principle also involves wages, since one’s income affects how one can support a family with respect.

- Social Justice: Here the concerns listed by the Archbishop include: welfare policy, religious freedom, Social Security, affordable health care, and sharing housing and the resources of the earth with the poor. He also includes the reform of the criminal justice system, and the issue of immigration (“welcoming the stranger). Not only must the immigrant be treated with dignity, the Archbishop correctly observes that “the Catholic Church teaches that people, under certain circumstances, have a right to leave their country and find a new life.” Other social justice issues involve respect for the environment and using the environment in a way that promotes respect for humanity.

- Global Solidarity: Finally, the Archbishop asks, “what is the candidate willing to do to foster solidarity, for the elimination of global poverty, for religious liberty and human rights? We must ask how the person will work with the United Nations and international bodies.

Archbishop Aymond is a realist who recognizes that “it is likely that no candidate will measure up to all four completely.” What is the Catholic citizen to do? He answers:

We have to decide which of them would best move our country forward in a way that reflects those qualities. We as Catholics must have our voice heard: We are tired of the lack of civility that exists in campaigns and we are calling for change.

So, as much as we might be tempted to “give up politics” for Lent this year, as human beings (and therefore “political animals” as the Pope cites Aristotle) we cannot; as Christians we must not. In fact, I think we can add to the Aristotelian reference and find this moral obligation highlighted even more. In his Politics, the fourth century BC philosopher writes:

So, as much as we might be tempted to “give up politics” for Lent this year, as human beings (and therefore “political animals” as the Pope cites Aristotle) we cannot; as Christians we must not. In fact, I think we can add to the Aristotelian reference and find this moral obligation highlighted even more. In his Politics, the fourth century BC philosopher writes:

Hence it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal. And he who by nature and not by mere accident is without a state, is either above humanity, or below it. . . . he may be compared to a bird which flies alone.

Now the reason why man is more of a political animal than bees or any other gregarious animals is evident. Nature, as we often say, makes nothing in vain, and man is the only animal whom she has endowed with the gift of speech. And. . . the power of speech is intended to set forth the expedient and inexpedient, and likewise the just and the unjust. And it is a characteristic of man that he alone has any sense of good and evil, of just and unjust, and the association of living beings who have this sense makes a family and a state.

As difficult as it can be, therefore, we have a moral obligation to participate in the political process. We cannot say that we are “above” it or that we are presented with no other moral option than to withdraw. The greater good — the common good — demands that we do the best we can on behalf of others as well as ourselves, as expressed in the greatest Commandment given by Christ: to love God and to love others as we love ourselves.

A word about clergy and politics. I have written about this previously, but I want to recap three points here.

A word about clergy and politics. I have written about this previously, but I want to recap three points here.

- Clergy and Social Media: Clergy of all faiths are prominent in their use of social media and are blogging, tweeting, writing, speaking and teaching at every conceivable level, and even venues formerly considered more informal, such as Facebook. It is important to reflect on our own participation in such exchanges in light of our responsibilities as clergy. It is often not what we say, or don’t say, from the pulpit that can influence others, but our casual “status update” on Facebook, a blog entry or even a tweet can have far-reaching effects.

- Catholic Clergy and Canon Law: Canon 285 directs that “clerics are to refrain completely from all those things which are unbecoming to their state, according to the prescripts of particular law.” The canon continues in §3: “Clerics are forbidden to assume public offices which entail a participation in the exercise of civil power,” and §4 forbids clerics from “secular offices which entail an obligation of rendering accounts. . . .” Canon 287, §1 reminds all clerics that “most especially, [they] are always to foster the peace and harmony based on justice which are to be observed among people,” and §2 directs that “they are not to have an active part in political parties and in governing labor unions unless, in the judgment of competent ecclesiastical authority, the protection of the rights of the Church or the promotion of the common good requires it.” However, c. 288 specifically relieves permanent deacons (transitional deacons would still bound) of a number of the prior canons, including cc. 285 §§3 and 4, and 287 §2, “unless particular law establishes otherwise.” Particular law in this instance is provided by the National Directory on the Formation, Ministry and Life of Permanent Deacons in the United States, which states at #91: “A permanent deacon may not present his name for election to any public office or in any other general election, or accept a nomination or an appointment to public office, without the prior written permission of the diocesan bishop. A permanent deacon may not actively and publicly participate in another’s political campaign without the prior written permission of the diocesan bishop.” While we are each entitled to form our own political decisions for ourselves, we must always be aware of the political lines we must not cross. Much more about this can be said and I will review all of this in more detail in a later posting.

- Unique Political Position for Catholic [Permanent] Deacons: As we just saw, permanent deacons may participate in political life to a degree not permitted other clerics (including transitional deacons) under the law. However, permanent deacons are required by particular law in the United States to obtain the prior written permission of their diocesan bishop to do so. I find that two other aspects of this matter are too often overlooked. First, is the requirement under the law that all clerics (and, significantly, permanent deacons are not relieved of this obligation) are bound by c. 287 always “to foster peace and harmony based on justice.” This is such a critical point for reflection for all clerics: How do my actions, words, and insinuations foster such peace and harmony, or are my actions serving to sow discord and disharmony? Second is the whole area of participation in political campaigns. Deacons may only participate in their own or someone else’s political campaign with the prior written permission of their bishop. Today, when political support is often reflected through the social media, all of us might well reflect on how our opinions stated via these media constitute active participation in someone’s political campaign.

In concluding this Lenten reflection on Catholics and political life, I return to Archbishop Aymond’s fine column one last time. His own frustration is almost palpable as he ponders what the Church is supposed to do in the face of the contemporary political situation:

First of all, the church’s responsibility is to do what I am doing – speaking out and saying this is not what we want politics to be. It’s not of God. Where is our negativity bringing us? The second thing we should look at – helping people form their consciences so when they go to the voting machine, they know the basic qualities they are looking for in a candidate.

So, for Lent this year, let’s give up the vitriol, the name-calling, the demonizing of those who disagree with us. In fact, let’s go the other direction and increase and deepen our involvement in the political process as our state of life demands. In this season of purification and enlightenment, we must keep both of these elements in mind: to purify ourselves of that which demeans humanity and God’s creation, and to seek out and be enlightened by God so as to build up rather than to tear down.

“Christmas — who cares?”

“Christmas — who cares?” “I just get so depressed at Christmas. I’ve lost the innocence of youth and there’s no connection to family any more — and this just makes it all worse.”

“I just get so depressed at Christmas. I’ve lost the innocence of youth and there’s no connection to family any more — and this just makes it all worse.” In my Advent reflection yesterday on the Hebrew expression “Emmanuel” (God-with-us) I stressed the intimacy of this relationship with God. No matter how we may feel at any given moment, the God we have given our hearts to (which is actually the root meaning of “I believe”) is with us through it all — even when we can’t or don’t recognize it. Think of a child in her room playing. Does she realize that her father out in the kitchen is thinking about her, listening for sounds that may mean that she needs his help, pondering her future? Does she realize that her mother at work in her office is also thinking about her, loving her, and making plans for her future? The love of parents for children is constant and goes beyond simply those times when they are physically present to each other.

In my Advent reflection yesterday on the Hebrew expression “Emmanuel” (God-with-us) I stressed the intimacy of this relationship with God. No matter how we may feel at any given moment, the God we have given our hearts to (which is actually the root meaning of “I believe”) is with us through it all — even when we can’t or don’t recognize it. Think of a child in her room playing. Does she realize that her father out in the kitchen is thinking about her, listening for sounds that may mean that she needs his help, pondering her future? Does she realize that her mother at work in her office is also thinking about her, loving her, and making plans for her future? The love of parents for children is constant and goes beyond simply those times when they are physically present to each other. The world into which Jesus was born was every bit as violent, abusive, and full of destructive intent as our own. And yet, consider what Christians have maintained from the beginning. God’s saving plan was not brought about through noble families, through the Jewish high priestly caste, or through the structures of the Roman empire. It wasn’t engaged in Greek or Roman philosophies or religions. Instead we find a young Jewish girl from an ordinary family, her slightly older betrothed (there is nothing in scripture that suggests that Joseph was an older man, so we might assume that he was in his late teens, not that much older than Mary), shepherds (who were largely considered outcasts in Jewish society), foreign astrologers avoiding the puppet Jewish king, and on and on. What’s more, the savior of the world sent by God doesn’t show up on a white charger at the head of mighty army, but as a baby.

The world into which Jesus was born was every bit as violent, abusive, and full of destructive intent as our own. And yet, consider what Christians have maintained from the beginning. God’s saving plan was not brought about through noble families, through the Jewish high priestly caste, or through the structures of the Roman empire. It wasn’t engaged in Greek or Roman philosophies or religions. Instead we find a young Jewish girl from an ordinary family, her slightly older betrothed (there is nothing in scripture that suggests that Joseph was an older man, so we might assume that he was in his late teens, not that much older than Mary), shepherds (who were largely considered outcasts in Jewish society), foreign astrologers avoiding the puppet Jewish king, and on and on. What’s more, the savior of the world sent by God doesn’t show up on a white charger at the head of mighty army, but as a baby. And so we return to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This well-known German Lutheran theologian, pastor, and concentration camp martyr embodies the wedding of of the meaning of Christmas with the real world in which we live. He devoted his life to study, to writing, to opposing injustice — especially the Nazi regime in Germany, ultimately giving the ultimate witness to Christ. Christians like Bonhoeffer, whose best-known work is called The Cost of Discipleship, are not dreamy, wide-eyed innocents who do not connect with the world. In fact, their witness shows us just the opposite. The true Christian is one who — following Christ — engages the world in all of its joys, hopes, pains and suffering. It is with Bonhoeffer, then, that we enter into Christmas 2015, with his wonderful reflection:

And so we return to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This well-known German Lutheran theologian, pastor, and concentration camp martyr embodies the wedding of of the meaning of Christmas with the real world in which we live. He devoted his life to study, to writing, to opposing injustice — especially the Nazi regime in Germany, ultimately giving the ultimate witness to Christ. Christians like Bonhoeffer, whose best-known work is called The Cost of Discipleship, are not dreamy, wide-eyed innocents who do not connect with the world. In fact, their witness shows us just the opposite. The true Christian is one who — following Christ — engages the world in all of its joys, hopes, pains and suffering. It is with Bonhoeffer, then, that we enter into Christmas 2015, with his wonderful reflection:

Here is the final antiphon, assigned to 23 December. While the original texts of most of the “O Antiphons” were in Latin, here’s one that’s even more ancient (although Latin appropriated it later!). “Emmanuel” is a Hebrew word taken directly from the original text of Isaiah: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14).

Here is the final antiphon, assigned to 23 December. While the original texts of most of the “O Antiphons” were in Latin, here’s one that’s even more ancient (although Latin appropriated it later!). “Emmanuel” is a Hebrew word taken directly from the original text of Isaiah: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14).

O Morning Star,

O Morning Star,

The “O Antiphon” for 19 December begins “O Radix Jesse.” While some translations use the word, “flower” for the Latin “radix,” I prefer the more literal “root” because it signals clearly the Mystery being invoked in this prayer. The point of this ancient antiphon is to identify the coming Messiah as the very root and foundation of creation and covenant. Our connection to Christ and to the world is not a superficial grafting onto a minor branch of the family tree, but to the very root itself. We are grounded, connected and vitally linked to Christ.

The “O Antiphon” for 19 December begins “O Radix Jesse.” While some translations use the word, “flower” for the Latin “radix,” I prefer the more literal “root” because it signals clearly the Mystery being invoked in this prayer. The point of this ancient antiphon is to identify the coming Messiah as the very root and foundation of creation and covenant. Our connection to Christ and to the world is not a superficial grafting onto a minor branch of the family tree, but to the very root itself. We are grounded, connected and vitally linked to Christ. As ministers of the Church’s charity, justice and mercy, we deacons (this is, after all, a blog focused on the diaconate!) must lead in our concern for those who find themselves cut off from society and church and perhaps even cut off from that very Root of Jesse. Pope Francis, in Evangelium Gaudium condemns anything which contributes to such isolation of human beings. Even concerning economies, for example, he condemns any “economy of exclusion and inequality. How can it be that it is not a news item when as elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock mart loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrwon away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality” (#53). We are to be a people of INCLUSION AND EQUALITY, not exclusion and inequality.

As ministers of the Church’s charity, justice and mercy, we deacons (this is, after all, a blog focused on the diaconate!) must lead in our concern for those who find themselves cut off from society and church and perhaps even cut off from that very Root of Jesse. Pope Francis, in Evangelium Gaudium condemns anything which contributes to such isolation of human beings. Even concerning economies, for example, he condemns any “economy of exclusion and inequality. How can it be that it is not a news item when as elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock mart loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrwon away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality” (#53). We are to be a people of INCLUSION AND EQUALITY, not exclusion and inequality.

The pope’s message is quite clear and, when considered as part of our Advent reflection on “O Root of Jesse”, particularly on point. As Christians we thrive when we are grafted to the Messiah, the source of life. Our mission of mercy is to serve to graft others to the Messiah as well. Our faith is not merely expressed in a text — no matter how vital those texts are in themselves — but in the concrete encounter of one person with another. The pope even dares to use an expression often mocked by certain Catholics, the “spirit which emerged from Vatican II” and equates that spirit with the spirit that drove the Samaritan, the Samaritan who is our model for the mercy of God.

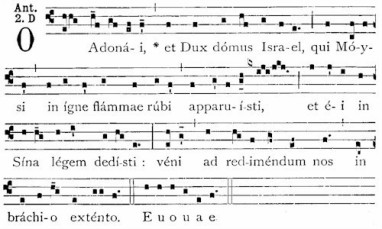

The pope’s message is quite clear and, when considered as part of our Advent reflection on “O Root of Jesse”, particularly on point. As Christians we thrive when we are grafted to the Messiah, the source of life. Our mission of mercy is to serve to graft others to the Messiah as well. Our faith is not merely expressed in a text — no matter how vital those texts are in themselves — but in the concrete encounter of one person with another. The pope even dares to use an expression often mocked by certain Catholics, the “spirit which emerged from Vatican II” and equates that spirit with the spirit that drove the Samaritan, the Samaritan who is our model for the mercy of God. The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived.

The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived. God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on: