4 July 2025

Commander William T. Ditewig, United States Navy (ret.)

Most citizens of the United States are disheartened by the current state of political affairs in our country. There appears to be no gradation of belief and opinion, no political “spectrum”: one is either at one polar end of this non-existent spectrum or the other. One extreme holds that we are doomed by the other extreme, that those who hold opposing views are ignorant, evil, disloyal, dangerous, and deadly to the principles of our founders. The opposing extreme holds the same. On a personal level, I recently wore my Navy uniform as part of a Memorial Day ceremony. I was actually taken to task by several loved ones for doing so, apparently because they felt I would be misunderstood as supporting one political entity over another. Still others have expressed such dismay over the current state of political and cultural affairs that they not only have no interest in celebrating the Fourth of July, but they actually oppose its observance altogether. Their distress has prompted me to consider the nature of true patriotism itself.

At the heart of this reflection is a motto used by our Navy and others when describing national service: “non sibi sed patriae” – “Not for self but for country.” In my twenty-two years of Naval service, and this is the point of view of many with whom I served, I rarely knew the political leanings of others in uniform. It was not something we saw as important in our service. We careerists, serving for decades, had many commanders-in-chief, often as different as night and day. It really mattered little since our service is to the Constitution, not to an individual, any individual, and certainly not to any political party, personality cult, or popular opinion. We were willing to put our lives on the line for each other and “in order to create a more perfect union.” It was never about awards, medals, or promotions. The higher one’s rank, the greater measure of service was expected, not for ourselves but for the country.

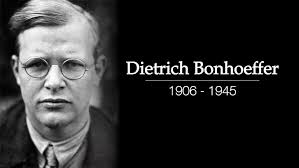

German Protestant pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, arrested, imprisoned, and eventually murdered in 1945 by the Nazis, wrote eloquently about many things, including what he called “the cost of discipleship.” One of his most widely quoted insights concerns his distinction between “cheap” and “costly” grace. According to Bonhoeffer, cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without repentance, baptism without discipline, communion without confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ. Regardless of one’s religious beliefs, I think all can appreciate the notion that our beliefs about anything carry with them a responsibility to act accordingly, that our beliefs are more than simple “cheap” words, devoid of concrete impact.

It strikes me that one might make a similar distinction between “cheap” patriotism and “costly” patriotism. Cheap patriotism is the jingoistic bluster of the bully, toxic forms of masculinity, and appeals to violence as a first resort rather than the last. This is not true patriotism. It is demagoguery. Costly patriotism looks beyond all of that. The cost of true patriotism is found in acting despite one’s own fear of injury or death, of realizing that there are people and principles more important than oneself, people and principles worth dying for.

Cheap patriotism is about waving the flag without honor. Cheap patriotism holds loyalty to a leader as a prime virtue. Cheap patriotism wears the uniform as a sign of personal status. Costly patriotism is about the people of the country, not an individual. Costly patriotism never lets the flag we honor “touch the ground” of personal greed, political posturing, or be used as a tool of violent revolt. As I watched in horror the events of January 6, 2021, two images still haunt me. First was the use of the flag as a weapon, as a tool of violence in every sense of those words. Second was watching others replace the flag of our country with a personal “flag” of the man who had lost the presidential election: he was being elevated, literally, above our own national ensign. Such cheap patriotism should have no place in our country, a country founded on principles of service over self.

This brings us back to the Fourth of July. If we let those who proclaim “cheap” patriotism have their way, we lose as a country and as individuals. If we don’t remember and celebrate “costly” patriotism, the bullies win. On the other hand, if we do remember and celebrate true and costly patriotism, we proclaim in word and deed that we are more than our worst instincts, more than empty posturing, and that we will redouble our efforts, individually and collectively, to create the more perfect union our Constitution calls us to. For me, personally, this is what it means to wear the uniform of my country’s Navy again. It connects me with the generations of family and friends who have shared that same commitment to service over self.

On this Fourth of July, may we take time to reflect on costly patriotism: “non sibi sed patriae”. And after reflection, action.