“Christmas — who cares?”

“Christmas — who cares?”

“It’s for the kids; I’m too old for that nonsense.”

“Christians are all hypocrites anyway.”

“I used to be a Catholic; then I grew up.”

“It’s all about the money: the malls, the churches: all the same.”

“I just get so depressed at Christmas. I’ve lost the innocence of youth and there’s no connection to family any more — and this just makes it all worse.”

“I just get so depressed at Christmas. I’ve lost the innocence of youth and there’s no connection to family any more — and this just makes it all worse.”

“With all of the violence and craziness in the world, why the hell should I get involved with all this make-believe?

As we enter another Christmas Season (and remember that for Christians, Christmas Day is just the beginning of a whole season of “Christmas”!), perhaps we should reflect a bit on why we even care about it. “Christmas” as an event has just become, for so many people, a civic holiday, a commercial opportunity, and mere Seinfeldian “festivus”. Let’s face it: for many people, “Christmas” is simply something to be endured and survived.

Why do Christians care about Christmas? What does it — what should it — mean? Are Christians who celebrate Christmas simply naive children who won’t grow up?

In my Advent reflection yesterday on the Hebrew expression “Emmanuel” (God-with-us) I stressed the intimacy of this relationship with God. No matter how we may feel at any given moment, the God we have given our hearts to (which is actually the root meaning of “I believe”) is with us through it all — even when we can’t or don’t recognize it. Think of a child in her room playing. Does she realize that her father out in the kitchen is thinking about her, listening for sounds that may mean that she needs his help, pondering her future? Does she realize that her mother at work in her office is also thinking about her, loving her, and making plans for her future? The love of parents for children is constant and goes beyond simply those times when they are physically present to each other.

In my Advent reflection yesterday on the Hebrew expression “Emmanuel” (God-with-us) I stressed the intimacy of this relationship with God. No matter how we may feel at any given moment, the God we have given our hearts to (which is actually the root meaning of “I believe”) is with us through it all — even when we can’t or don’t recognize it. Think of a child in her room playing. Does she realize that her father out in the kitchen is thinking about her, listening for sounds that may mean that she needs his help, pondering her future? Does she realize that her mother at work in her office is also thinking about her, loving her, and making plans for her future? The love of parents for children is constant and goes beyond simply those times when they are physically present to each other.

God is like that, too. Sometimes we feel God’s presence around us, sometimes we don’t. From our perspective it might seem like God has left us — but God hasn’t. That’s the beauty of “Emmanuel” and the great insight of the Jewish people which we Christians have inherited: regardless of what I may think or feel at any given moment, “God is with us.”

Christmas celebrates that reality. But there’s more to it than that. God isn’t with us as some kind of superhero god with a deep voice and stirring sound track like a Cecil B. De Mille biblical epic. God “thinks big and acts small” and comes to the world as a weak and helpless baby. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote, “God is in the manger.” We’ll have more to say about that in a moment. But for now, consider the mistake that many people make. As we get older and set aside childish ways, some people assume that since God is in the manger as a baby, that this makes Christmas simply something for children. How wrong they are! The great scripture scholar, the late Raymond Brown, emphasized this point in his landmark study, “An Adult Christ at Christmas.” If you haven’t read it, I strongly recommend you do so: consider it a belated Christmas gift to yourself!

The world into which Jesus was born was every bit as violent, abusive, and full of destructive intent as our own. And yet, consider what Christians have maintained from the beginning. God’s saving plan was not brought about through noble families, through the Jewish high priestly caste, or through the structures of the Roman empire. It wasn’t engaged in Greek or Roman philosophies or religions. Instead we find a young Jewish girl from an ordinary family, her slightly older betrothed (there is nothing in scripture that suggests that Joseph was an older man, so we might assume that he was in his late teens, not that much older than Mary), shepherds (who were largely considered outcasts in Jewish society), foreign astrologers avoiding the puppet Jewish king, and on and on. What’s more, the savior of the world sent by God doesn’t show up on a white charger at the head of mighty army, but as a baby.

The world into which Jesus was born was every bit as violent, abusive, and full of destructive intent as our own. And yet, consider what Christians have maintained from the beginning. God’s saving plan was not brought about through noble families, through the Jewish high priestly caste, or through the structures of the Roman empire. It wasn’t engaged in Greek or Roman philosophies or religions. Instead we find a young Jewish girl from an ordinary family, her slightly older betrothed (there is nothing in scripture that suggests that Joseph was an older man, so we might assume that he was in his late teens, not that much older than Mary), shepherds (who were largely considered outcasts in Jewish society), foreign astrologers avoiding the puppet Jewish king, and on and on. What’s more, the savior of the world sent by God doesn’t show up on a white charger at the head of mighty army, but as a baby.

God enters the scene in all the wrong places and in all the wrong ways. How will this “save” anyone?

God saves by so uniting himself with us (Emmanuel) that he takes on all of our struggles, joys, pains, and hopes. The ancient hymn, quoted by that former and infamous persecutor of Christians, Saul-who-became-Paul, captures it well (Philippians 2: 5-11):

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

6 who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

7 but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

8 he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

9 Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,

10 so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

11 and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

What should all of this nice poetry mean to us? Paul is explicit. Writing from prison himself, he tells the Philippians: “Be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. 3 Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. 4 Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others.” This self-emptying is called kenosis in Greek, and the path of the Christian, following Christ, is first to empty ourselves if we hope later to rise with him.

THIS IS THE VERY HEART OF CHRISTIANITY AND WHAT IT MEANS TO CALL OURSELVES DISCIPLES OF JESUS THE CHRIST: TO EMPTY OURSELVES IN IMITATION OF CHRIST. IF WE’RE NOT DOING THAT WE DARE NOT CALL OURSELVES “CHRISTIANS”!

Many people have written about this in a variety of contexts. Here are just a few random examples.

Empty yourself: “Suffering and death can express a love which gives itself and seeks nothing in return.” John Paul II, Fides et Ratio, #93.

Empty yourself: “The gift to us of God’s ever faithful love must be answered by an authentic life of charity which the Holy Spirit pours into our hearts. We too must give our gift fully; that is, we must divest ourselves of ourselves in that same kenosis of love.” Jean Corbon, The Wellspring of Worship, 107.

Empty yourself: “Kenosis moves beyond simply giving up power. It is an active emptying, not simply the acceptance of powerlessness.” William Ditewig, The Exercise of Governance by Deacons: A Theological and Canonical Study.

Empty yourself: “It is precisely in the kenosis of Christ (and nowhere else) that the inner majesty of God’s love appears, of God who ‘is love’ (1 John 4:8) and a ‘trinity.’ Hans Urs von Balthasar, Love Alone.

Empty yourself: “Satan fears the Trojan horse of an open human heart.” Johann Baptist Metz, Poverty of Spirit.

And so we return to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This well-known German Lutheran theologian, pastor, and concentration camp martyr embodies the wedding of of the meaning of Christmas with the real world in which we live. He devoted his life to study, to writing, to opposing injustice — especially the Nazi regime in Germany, ultimately giving the ultimate witness to Christ. Christians like Bonhoeffer, whose best-known work is called The Cost of Discipleship, are not dreamy, wide-eyed innocents who do not connect with the world. In fact, their witness shows us just the opposite. The true Christian is one who — following Christ — engages the world in all of its joys, hopes, pains and suffering. It is with Bonhoeffer, then, that we enter into Christmas 2015, with his wonderful reflection:

And so we return to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. This well-known German Lutheran theologian, pastor, and concentration camp martyr embodies the wedding of of the meaning of Christmas with the real world in which we live. He devoted his life to study, to writing, to opposing injustice — especially the Nazi regime in Germany, ultimately giving the ultimate witness to Christ. Christians like Bonhoeffer, whose best-known work is called The Cost of Discipleship, are not dreamy, wide-eyed innocents who do not connect with the world. In fact, their witness shows us just the opposite. The true Christian is one who — following Christ — engages the world in all of its joys, hopes, pains and suffering. It is with Bonhoeffer, then, that we enter into Christmas 2015, with his wonderful reflection:

Who among us will celebrate Christmas correctly? Whoever finally lays down all power, all honor, all reputation, all vanity, all arrogance, all individualism beside the manger; whoever remains lowly and lets God alone be high; whoever looks at the child in the manger and sees the glory of God precisely in his lowliness.

MAY WE ALL “GET” CHRISTMAS THIS YEAR! HOW WILL WE EMPTY OURSELVES FOR OTHERS?

MERRY CHRISTMAS!

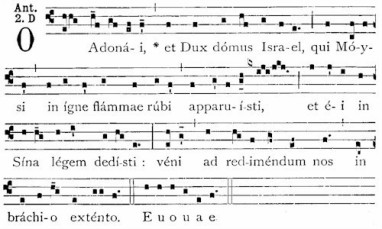

Here is the final antiphon, assigned to 23 December. While the original texts of most of the “O Antiphons” were in Latin, here’s one that’s even more ancient (although Latin appropriated it later!). “Emmanuel” is a Hebrew word taken directly from the original text of Isaiah: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14).

Here is the final antiphon, assigned to 23 December. While the original texts of most of the “O Antiphons” were in Latin, here’s one that’s even more ancient (although Latin appropriated it later!). “Emmanuel” is a Hebrew word taken directly from the original text of Isaiah: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14).

O Morning Star,

O Morning Star,

The “O Antiphon” for 19 December begins “O Radix Jesse.” While some translations use the word, “flower” for the Latin “radix,” I prefer the more literal “root” because it signals clearly the Mystery being invoked in this prayer. The point of this ancient antiphon is to identify the coming Messiah as the very root and foundation of creation and covenant. Our connection to Christ and to the world is not a superficial grafting onto a minor branch of the family tree, but to the very root itself. We are grounded, connected and vitally linked to Christ.

The “O Antiphon” for 19 December begins “O Radix Jesse.” While some translations use the word, “flower” for the Latin “radix,” I prefer the more literal “root” because it signals clearly the Mystery being invoked in this prayer. The point of this ancient antiphon is to identify the coming Messiah as the very root and foundation of creation and covenant. Our connection to Christ and to the world is not a superficial grafting onto a minor branch of the family tree, but to the very root itself. We are grounded, connected and vitally linked to Christ. As ministers of the Church’s charity, justice and mercy, we deacons (this is, after all, a blog focused on the diaconate!) must lead in our concern for those who find themselves cut off from society and church and perhaps even cut off from that very Root of Jesse. Pope Francis, in Evangelium Gaudium condemns anything which contributes to such isolation of human beings. Even concerning economies, for example, he condemns any “economy of exclusion and inequality. How can it be that it is not a news item when as elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock mart loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrwon away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality” (#53). We are to be a people of INCLUSION AND EQUALITY, not exclusion and inequality.

As ministers of the Church’s charity, justice and mercy, we deacons (this is, after all, a blog focused on the diaconate!) must lead in our concern for those who find themselves cut off from society and church and perhaps even cut off from that very Root of Jesse. Pope Francis, in Evangelium Gaudium condemns anything which contributes to such isolation of human beings. Even concerning economies, for example, he condemns any “economy of exclusion and inequality. How can it be that it is not a news item when as elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock mart loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrwon away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality” (#53). We are to be a people of INCLUSION AND EQUALITY, not exclusion and inequality.

The pope’s message is quite clear and, when considered as part of our Advent reflection on “O Root of Jesse”, particularly on point. As Christians we thrive when we are grafted to the Messiah, the source of life. Our mission of mercy is to serve to graft others to the Messiah as well. Our faith is not merely expressed in a text — no matter how vital those texts are in themselves — but in the concrete encounter of one person with another. The pope even dares to use an expression often mocked by certain Catholics, the “spirit which emerged from Vatican II” and equates that spirit with the spirit that drove the Samaritan, the Samaritan who is our model for the mercy of God.

The pope’s message is quite clear and, when considered as part of our Advent reflection on “O Root of Jesse”, particularly on point. As Christians we thrive when we are grafted to the Messiah, the source of life. Our mission of mercy is to serve to graft others to the Messiah as well. Our faith is not merely expressed in a text — no matter how vital those texts are in themselves — but in the concrete encounter of one person with another. The pope even dares to use an expression often mocked by certain Catholics, the “spirit which emerged from Vatican II” and equates that spirit with the spirit that drove the Samaritan, the Samaritan who is our model for the mercy of God. The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived.

The “O Antiphons” are titles to be associated with the Messiah, the Anointed One; on 18 December, the Messiah is linked to the Lord of Israel who saved Israel. The connection continues through the allusion to Moses, called to lead the people to freedom in God’s name, and to whom God would give the Torah on Sinai. Although in English we tend to interpret “law” in a sense of “rules”, that is not the way it is understood in Hebrew and the Jewish tradition. Torah refers to instruction or teaching. In the covenant relationship with God, these instructions describe the practical nature of how the covenant is to be lived. God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

God’s part of the covenant is to rescue us. When Pope Francis promulgated Misericordiae Vultus announcing the Extraordinary Year of Mercy, he chose to evoke this scene of the all-powerful God with Moses:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on:

The Church, the pope reminds his readers, is always open because God is always open to all. “The Church is called to be the house of the Father, with doors always wide open” (#47). In addressing the pastoral consequences of this radical openness, the pope tackles a current issue head on:

Today in Rome the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with Jews released a new document exploring unresolved theological questions at the heart of Christian-Jewish dialogue. According to Vatican Radio,

Today in Rome the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with Jews released a new document exploring unresolved theological questions at the heart of Christian-Jewish dialogue. According to Vatican Radio, It has been a distinct privilege for me over the years to serve as a Hebrew linguist in a variety of contexts, and five years ago I was asked by the Center for Catholic-Jewish Studies to give a very brief reflection on “The Significance of Nostra Aetate” on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of its promulgation by the Second Vatican Council. So what I am about to write should not be read in any way as a criticism of the great efforts that have been made over the past fifty years to celebrate the relationship of Jews and Catholics! And, as the new document released today underscores, so much more remains to be done in this regard, and I fully embrace that effort.

It has been a distinct privilege for me over the years to serve as a Hebrew linguist in a variety of contexts, and five years ago I was asked by the Center for Catholic-Jewish Studies to give a very brief reflection on “The Significance of Nostra Aetate” on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of its promulgation by the Second Vatican Council. So what I am about to write should not be read in any way as a criticism of the great efforts that have been made over the past fifty years to celebrate the relationship of Jews and Catholics! And, as the new document released today underscores, so much more remains to be done in this regard, and I fully embrace that effort. Let’s take a closer look at the document itself. Much has been written about the genesis of the document, so there is no need to rehearse all of that here. Suffice it to say that Nostra Aetate, in the final analysis, is not the work of one person, as influential as so many individuals were in its inception and development: John XXIII himself, Jules Isaac, Augustin Bea, to name just a few.

Let’s take a closer look at the document itself. Much has been written about the genesis of the document, so there is no need to rehearse all of that here. Suffice it to say that Nostra Aetate, in the final analysis, is not the work of one person, as influential as so many individuals were in its inception and development: John XXIII himself, Jules Isaac, Augustin Bea, to name just a few. The reason that Pope John called the Council in the first place was so that all the bishops from around the world could together tackle the very real life and death issues that were affecting all people, not just Catholics. This was not some simple superficial ceremonial event; it was, in fact, an attempt to make faith in God something transformative so that the world would never again find itself in the midst of the tragedies of the first half of the 20th century. It is in this light, then, that the significance of Nostra Aetate must be seen.

The reason that Pope John called the Council in the first place was so that all the bishops from around the world could together tackle the very real life and death issues that were affecting all people, not just Catholics. This was not some simple superficial ceremonial event; it was, in fact, an attempt to make faith in God something transformative so that the world would never again find itself in the midst of the tragedies of the first half of the 20th century. It is in this light, then, that the significance of Nostra Aetate must be seen. So far, then, the Council is focused on all people. Now, in paragraph #2 the bishops turn to people who have found “a certain perception of that hidden power which hovers over the course of things and over the events of human history; at times some indeed have come to the recognition of a Supreme Being, or even of a Father. This perception and recognition penetrates their lives with a profound religious sense.” These comments apply to a wide variety of religious expression, from various Eastern forms to Native American and on and on. Then they turn specifically to certain Eastern religions:

So far, then, the Council is focused on all people. Now, in paragraph #2 the bishops turn to people who have found “a certain perception of that hidden power which hovers over the course of things and over the events of human history; at times some indeed have come to the recognition of a Supreme Being, or even of a Father. This perception and recognition penetrates their lives with a profound religious sense.” These comments apply to a wide variety of religious expression, from various Eastern forms to Native American and on and on. Then they turn specifically to certain Eastern religions: Buddhism, in its various forms, realizes the radical insufficiency of this changeable world; it teaches a way by which people, in a devout and confident spirit, may be able either to acquire the state of perfect liberation, or attain, by their own efforts or through higher help, supreme illumination.

Buddhism, in its various forms, realizes the radical insufficiency of this changeable world; it teaches a way by which people, in a devout and confident spirit, may be able either to acquire the state of perfect liberation, or attain, by their own efforts or through higher help, supreme illumination. Paragraph #3 specifically addresses Islam:

Paragraph #3 specifically addresses Islam: And in language made even more poignant over the last generation, the bishops write:

And in language made even more poignant over the last generation, the bishops write: